Search for articles or browse our knowledge portal by topic.

Pavement Preservation Basics

Newly constructed pavements typically remain in good condition for a few years before exposure to traffic and weathering causes deterioration to set in. When left untreated, deterioration accelerates as pavement ages.

Figure 1 represents an asset management strategy in which pavement deteriorates to a poor condition before remediation measures (typically resurfacing or rehabilitation) are applied. This is referred to as a worst-first strategy because during project prioritization roads in the worst condition receive the highest priority.

While this strategy may seem intuitive, most transportation agencies have found applying it at the network level is unsustainable because there is not enough funding for preservation. Waiting until pavements are in poor condition to pursue corrective action is more expensive due to the level of effort and amount of material required. Most agencies lack the funding to address their needs quickly enough to prevent the backlog of poor pavements from growing longer as pavements age and deteriorate.

An ostensibly simple solution is to increase funding so a worst-first strategy can be effective. However, this ignores several realities pavement management engineers face:

- Competing needs for safety, operations, and economic development always constrain preservation budgets.

- Agencies must be able to show their use of available funding is efficient if the public is to support increased funding.

- Even if adequate funding is provided, agencies employing a worst-first approach must accept that pavements are not addressed until they are in poor condition. This requires the public to endure a lower overall level of service at a higher cost.

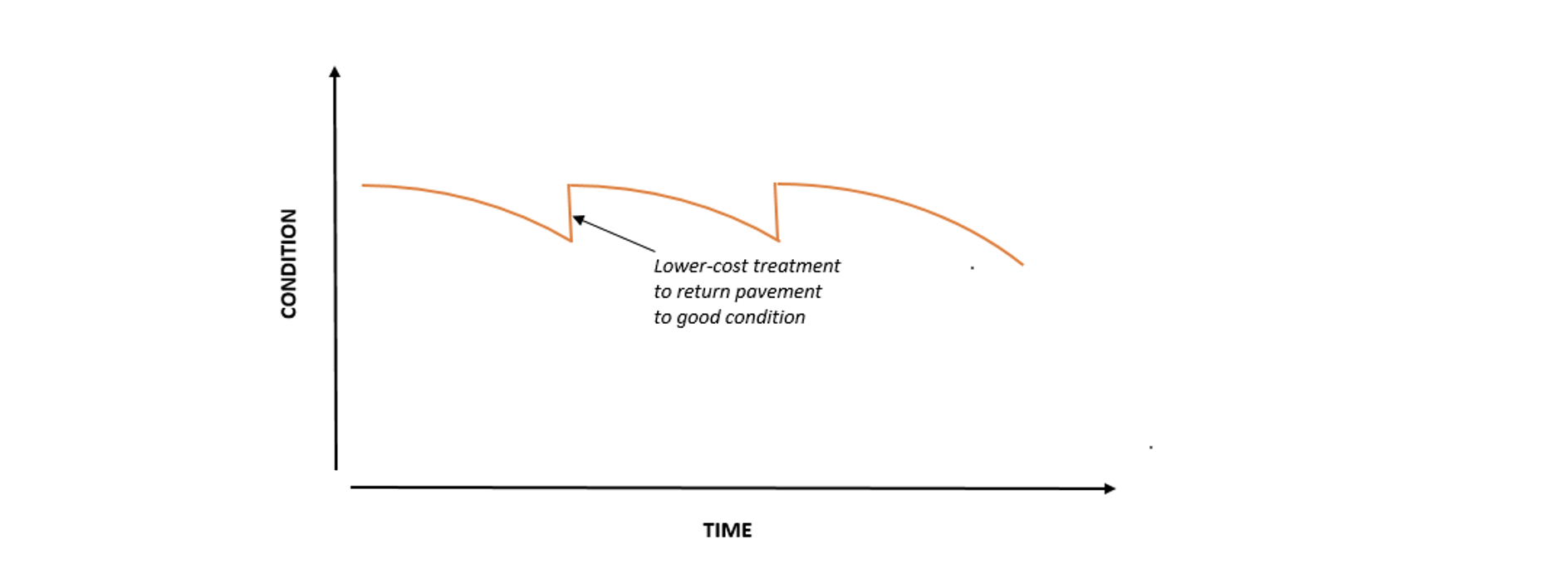

When agencies adopt a pavement preservation strategy, they implement less expensive preventive treatments earlier in the pavement life cycle that return pavement like-new condition. Along with being less expensive, consistent application of preventive treatments results in more consistent conditions across the pavement life cycle.

Preventive maintenance activities generally do not add capacity or structural value, however, they restore pavement to a better condition. The table below lists some of the common preventive maintenance treatments used by KYTC on asphalt pavements along with the recommended level of general surface distress which each treatment can be expected to address.

When evaluating whether to apply a given preventive maintenance treatment, additional factors beyond the condition of the existing pavement should be taken into consideration. The table below identifies some of the major advantages and disadvantages of the most common preventive maintenance treatments used by KYTC for asphalt pavements.

| Treatment | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Fog Seal | Very low cost. Locks in loose aggregate on chip seals. Increases visibility of striping and provides improved appearance. | May initially reduce skid resistance. Extended time to return to traffic. Proper application rate is critical. |

| Rejuvenators | Low cost, easy application. Slows oxidation of pavement. Good for treatment of shoulders. | Extended time to return to traffic. Proper application rate is critical. |

| Scrub Seal | Can improve friction. Slows oxidation of pavement. Quick and inexpensive seal for low to moderate severity cracks. Provides new wearing surface. | Increased pavement noise. Asphalt bleeding, flushing, and loose aggregate are possible if applied incorrectly. More difficult construction process. Striping may need to be performed multiple times. |

| Chip Seal | One of the most cost-effective pavement treatments. Improves skid, seals minor cracks, slows oxidation of pavement, and provides a new wearing surface. | Asphalt bleeding, flushing, and loose aggregate are possible if applied incorrectly. More difficult construction process. Striping may need to be performed multiple times. |

| Thinlay | Improves friction and ride. Reduces ravelling and noise. Aligns with expectations of drivers familiar with typical hot-mix asphalt surfaces. | Hand work can have an undesirable appearance. More attention required at asphalt plant to reduce oversize aggregate in mix. Quantity overruns can occur with minor roadway deflection. |

| Microsurface | Seals surface and addresses moderate distresses. Can be used to fill ruts. Results in a very high friction surface. Quick return to traffic. | Hand work can have an undesirable appearance. Side road approaches are more difficult to construct. Striping may need to be performed multiple times. Aggregate availability and space for staging areas can be problematic. |

| Cape Seal | Applicable on highly-distressed pavements. Provides long-lasting surface. Slows reflective cracking. | Initial chip seal application must thoroughly cure (48 hours to one week). Extra effort is needed to sweep chip seal prior to final surface application. |

Realizing the benefits of pavement preservation does not require that an agency only perform preventive treatments. An effective pavement preservation program invests in three types of activities: preventive maintenance, minor rehabilitation (non-structural), and routine maintenance (Figure 3).

Minor Rehabilitation “consists of structural enhancements that both extend the service life of an existing pavement and/or improve its load carrying capability” Source: AASHTO Highway Subcommittee on Maintenance Definition

Preventive Maintenance is “a planned strategy of cost effective treatments to an existing roadway system and its appurtenances that preserves the system, retards future deterioration, and maintains or improves the functional condition of the system without significantly increasing the structural capacity. Source: AASHTO Standing Committee on Highways, 1997

Routine Maintenance “consists of work that is planned and performed on a routine basis to maintain and preserve the condition of the highway system or to respond to specific conditions and events that restore the highway system to an adequate level of service.” Source: AASHTO Highway Subcommittee on Maintenance

How an agency allocates funding among these treatment types varies based on total available funding, network conditions, and industry capacity.

Equally important for understanding pavement preservation is recognizing what types of actions do not count as preservation:

Corrective Maintenance — Activities performed when a deficiency develops that negatively impacts the safe, efficient operations of the facility and future integrity of the pavement section.

Catastrophic Maintenance — Activities generally necessary to return a roadway facility to a minimum level of service while permanent restoration is designed and scheduled.

Pavement Reconstruction — The removal and replacement of the entire existing pavement structure by installing a pavement structure capable of carrying equivalent or increased traffic loads.

In 2017, FHWA’s Pavement Preservation Expert Task Group (PPETG) identified 10 characteristics of a world-class pavement preservation program. This information was later published in a series of articles in the Pavement Preservation Journal (PPJ). KYTC was featured in one of the articles, which highlighted the support that the preservation program had attained from leadership within the cabinet. The 10 characteristics discussed by FHWA are summarized below (this list first appeared in the Winter 2017 edition of the PPJ).

1. Provide dedicated and consistent funding.

Dedicated and consistent funding is needed so that preservation actions can be scheduled at the right time in the pavement’s condition cycle and to develop and maintain a healthy contracting workforce — contractors need to be able to plan for a stream of work, acquire equipment, and develop their workforce around expected projects.

2. All levels within the agency support the program.

Agencywide support is critical for effective implementation. Senior leadership must understand the benefits of and champion the program, local decision makers must be able to address constituent concerns, and staff overseeing preservation projects must grasp the program’s value and be able to ensure projects are constructed properly.

3. Base project selection and execution on objective data and proven guidelines.

Agencies can build and maintain program support by demonstrating that projects are selected using an objective methodology that identifies how the use of specific treatments is linked to assessments of pavement condition, traffic levels, and other factors. Initially, agencies may need to rely on regional or national research on cost and performance. As a program matures and staff gain knowledge of the performance and cost of specific treatments, guidelines must evolve to reflect that local knowledge. As a result, not every agency will have the same guidance for their selection process.

4. Use a variety of treatments that cover a range of conditions to address pavement preservation needs.

A successful program has a range of treatment options along with appropriate selection criteria. Funding must be flexible enough to let agencies experiment with new treatments. Agencies need to have options that allow for the application of treatments throughout the pavement life cycle rather than just near its end.

5. Assign knowledgeable agency and contract personnel to every preservation project.

Implementation of many preservation treatments demands real-time adjustments to achieve success. Contractors and/or agencies performing work need knowledgeable people onsite to make these adjustments. Agency inspectors must be knowledgeable and able to identify issues and verify the quality of the preservation treatment. Having one or two trained employees back at the office is not sufficient.

6. Use a pavement management system to track distress, identify current and future preservation needs, and pinpoint candidate roadways for preservation.

A pavement management system (PMS) can be used to track distresses over time and lets agencies move beyond a 1-year action plan to a 3- to 5-year plan. Agencies with a PMS can strategically plan their use of maintenance and preservation funds. For example, they may rework shoulders and ditches and crack seal two years before preservation, do minor patching one year before preservation, and complete the cycle with a surface treatment or thin overlay in the third year. Agencies that lack a sophisticated PMS program can still be successful if they measure and track pavement performance and maintain detailed treatment application and cost data.

7. Integrate pavement preservation into the agency’s asset management plan.

The Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21) and Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act (FAST ACT) required that states develop asset management plans outlining how they will fund and maintain infrastructure over a 10-year period. Agencies must conduct risk analyses, gap analysis, and life cycle cost analysis when developing their plan. The life cycle cost should demonstrate the benefit of preservation and can be key to closing the funding gap between existing funds and the cost of maintaining existing infrastructure.

8. Educate stakeholders about the benefits of the pavement preservation program and treatments.

Citizens understand that cars and homes require maintenance, but may overlook the maintenance and preservation needs of pavements and roadways. Thus, education is critical to garnering public support. Agencies should leverage interactions with stakeholders to not simply answer their questions but also explain the agency’s preservation program. Agencies should also keep stakeholders informed of planned treatments to avoid complaints and tort claims while building trust with the community.

9. Establish has a well-documented material specifications, testing program, and approval process.

Contractors that understand expectations related to material specifications as well as testing and approval procedures can bid more confidently for preservation work. Well-documented specifications and testing procedures also eliminates uncertainty for the agency and contractor. This does not mean that specifications or testing procedures are carved in stone. Specifications that do not work as intended should be changed. If the approval process results in work being accepted that does not perform well, the agency needs to reassess its practices and ensure it measures items most closely related to long-term performance. Soliciting input from contractors and material suppliers can be helpful in developing usable specifications and testing programs.

10. Track performance of preservation treatments and use this information to modify preservation plans.

Agencies use pavement management tools to develop a long-term plan, which is then implemented using meaningful specifications and testing and approval procedures. Roadways are monitored to gauge if their performance meets the expectations established when the plan was developed. For example, if a plan anticipates a surface treatment will perform well for 7–8 years, but it only lasts 5–6 years, changes may be needed. Achieving the expected performance life may require improving material specifications or modifying construction processes. Or the treatment selection process may need to be reevaluated to account for reduced performance life.

Closing the loop between performance and design expectations is fundamental to a sound preservation program. This includes conducting forensic investigations of treatments that fail earlier than expected. Do not remove treatments from the toolbox because of a small number of failures. Instead, reevaluate projects where failures occur to learn from them and modify selection, specification, testing, or acceptance criteria so the treatment can be retained while minimizing risks.

KYTC has developed resources for inspectors working on preventive maintenance projects to assist with oversight of construction activities. Links to these documents are available below and on the Division of Construction’s website.

Distributor Verify Calibration Wooksheet.xlsx

Electronic Paver Calibration.xlsx

Mechanical Paver Calibration.xlsx

Quick Reference Guide for Microsurfacing.pdf

Quick Reference Guide for Chip Seals.pdf

Pavement Preservation Knowledge Book:

Access the complete Knowledge Book here: Pavement Preservation Knowledge Book

Next Article: 3.1 Fog Seal

Previous Article: Evolution of Pavement Preservation in Kentucky