Search for articles or browse our knowledge portal by topic.

Data Gathering

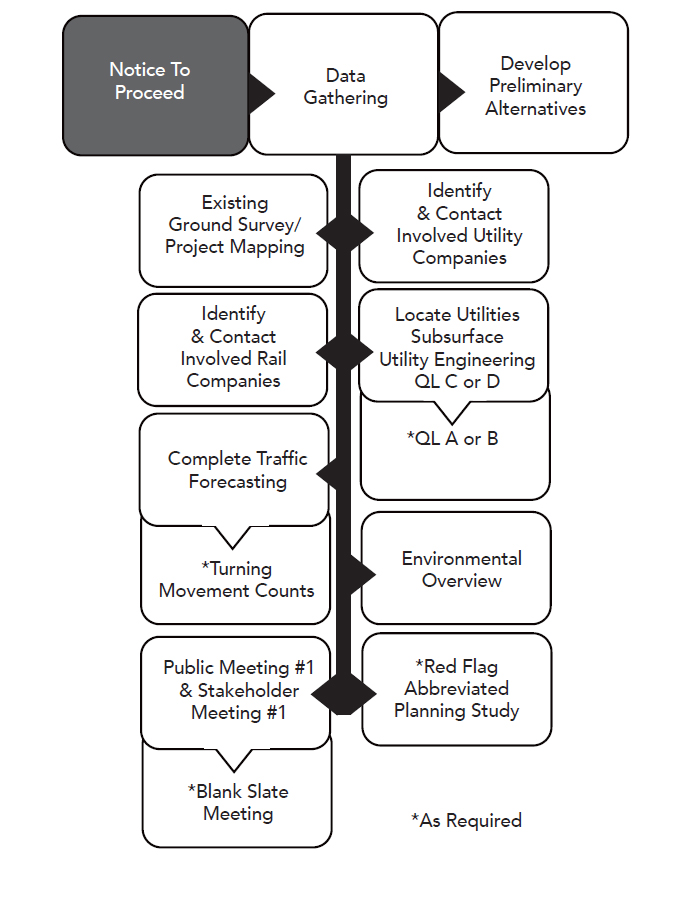

Contents

2. Existing Ground Survey/Project Mapping

3. Identify & Contact Involved Utility Companies

4. Locate Utilities – Subsurface Utility Engineering QL C or D

5. Locate Utilities – Subsurface Utility Engineering QL A or B (*If Required)

6. Identify and Contact Involved Rail Companies

7. Complete Traffic Forecasting

8. Turning Movement Counts (If Required)

10. Public Meeting #1 & Stakeholder Meeting #1

Upon receiving the Notice to Proceed, it is imperative for the PM to determine what additional data are needed to develop preliminary alternatives. Key information and features within the corridor should be identified and mapped before alignment studies begin. Without data on the study area, the study of alternatives may be flawed because the PDT will not understand the breadth and magnitude of project impacts and issues.

Early in the project, project mapping is assessed. (See entry HKP Project Time Management Article 2, Section 4, Assess Project Mapping.) At the beginning of Phase 1, available project data and mapping are reviewed to ensure sufficient coverage and identify additional data collection needs. Data collected from ground surveys are often necessary to locate additional existing features (e.g., underground facilities, obscured items, and measuring the sizes of pipes and invert elevations for inlets) and inform supplemental mapping.

During data collection and mapping, all existing property lines, ROW lines, easement lines, and KYTC permits and agreements within the project limits (and in some instances those in the general proximity of project limits) must be identified. All monuments and features that aid in the description of property lines should be located.

Red Flag

As with all field activities, ground survey crews should respect the rights of individual property owners and ask permission before entering their property. At minimum, a two-week notice should be given to property owners before entering their property.

Communication with utility companies should begin as early as possible in the project development process. Early coordination with impacted companies reduces the amount of risk to a project’s schedule and budget. During these communications, utility companies should be encouraged to identify methodologies that will either avoid impact to utility facilities, expedite facility relocations, or allow for the inclusion of relocation plans in the roadway plans. Early coordination may be appropriate to aid in the acquisition of parcels that will be necessary for the relocation of utility facilities or identify replacement utility easement needs.

Administered through the Division of Right of Way and Utilities, the Utility Conflict Matrix (UCM) can be used to document potential conflicts the preliminary roadway design may have with utility facilities in the project area. The UCM serves as an effective communication tool when discussing potential impacts with affected utility owners. For more detailed information on Utility Coordination and the Utility Conflict Matrix, see the Utilities & Rails Manual.

Utility companies should play an integral role in the design process and receive invitations to key meetings. At these meetings they can be advised of and consulted about impacts to their facilities from proposed roadway construction. The PDT’s selection of alternatives should account for information provided by utilities on where their facilities will face significant impacts in terms of time and cost. Using this knowledge, the PDT first attempts to avoid a conflict. If this is not possible, the team works to minimize and mitigate the conflict. Utility companies should also be invited to public involvement meetings so they can address the public directly.

Responsibility for identifying the location of existing facilities within the project limits lies with the PM. To obtain appropriate data, the PM should coordinate with the District Utility Agent during the early stages of project development. Locating existing utility facilities should occur as early as the Pre-Design and/or Conceptual Design phase (Phase 1), especially when there are large concentrations of facilities or a major utility facility.

Subsurface utility engineering (SUE) can be used to more accurately locate belowground facilities. The PM should determine what level of SUE quality is appropriate for various stages of project development. When making their assessment, the PM should also consider the quality level necessary to confirm a conflict with an existing utility of interest. Quality Level D (QL D) is information derived solely from existing records or verbal/written recollections. Quality Level C (QL C) is information obtained from surveying and plotting visible aboveground utility features and using professional judgment to corroborate this information with QL D information. When corridor studies are conducted to determine potential alternatives, the use of existing records or verbal information from utility companies will typically suffice.

For different stages of project development, the PM and PDT determine the appropriate SUE quality level. The quality level chosen should be commensurate with the potential for conflict and the given stage of project development. Therefore, specific areas in the project footprint may require a higher or lower SUE quality level than the project as a whole to address varying potentials for conflict. Discussions to identify affected facilities and their potential relocations should be initiated at this stage. The Highway Design Guidance Manual (HD-304) provides more information on subsurface utility location.

Side Note

KYTC’s KURTS app can be used at project sites to collect geospatial data on the location of existing utility facilities and to find potential conflicts with the proposed road. Geospatial data are used to create a utility conflict matrix that is stored with the project’s data. See the Utilities and Rails Guidance Manual for more information.

The required SUE quality level depends on the current stage of project development. During a corridor study to determine potential alternatives, the use of existing utility company records or verbal recollections will usually suffice. The quality level adopted to locate existing utility facilities should increase as a route is selected, refined, and designed in detail.

The required quality level also depends on potential impacts to complex utility networks (e.g., older networks or those with a high potential for costly facility relocations) or utility facilities that are consequential from the perspective of time and cost. If there is a significant probability of roadwork impacting such a facility and a highway can be designed to avoid that facility, it may be prudent to request early Quality Level A or B data, which provide accurate horizontal and (in the case of Quality Level A) vertical data at that location. An example of where this approach should be used is a complex utility facility on an urban highway project with existing ROW that is limited, narrow, and congested. The PM should identify specific areas in the project footprint that may require a confirmed horizontal and/or vertical location to address these specific locations of impactful utility conflicts.

Red Flag

As the Quality Level of utility location data increases, so does the coordination with utility owner. Collecting data for QL A or QL B efforts is only possible through close coordination with the utility owner. A SUE investigation, as described, can be paid for using D phase funds. An engineering agreement with a utility can also be paid for with D phase funds. U phase funds can be used for both engineering agreements and relocation, and can be authorized early where heightened coordination is needed during plan development. See the Highway Design Guidance Manual and Utilities and Rails Guidance Manual for additional information.

Any time a highway project can potentially impact a railroad, KYTC must coordinate with the railroad company. This includes projects that are at‐grade, over, or under railroad tracks as well as projects impacting railroad-owned property.

Rail coordination is an integral component of project development when a railroad is present. Undertaking railroad coordination activities early in project development fosters effective communication between KYTC and railroad companies and sets the stage for effective project collaboration. The PM may expect the railroad’s engineering review/approval of project details and ROW review/approval to occur separately. But individual railroads vary in their approaches. While delays and additional expenses are normal on projects with railroad involvement, early coordination helps minimize and manage the effects to KYTC’s schedule and budget. As an example, time-consuming and costly redesign work can be avoided if railroad expansions are planned and the PDT initiates an engineering review in time to adjust a preliminary structure layout. The PM should contact the Division of Right of Way and Utilities Railroad Coordinator as soon as possible, but no later than selection of the preferred alternative.

The Railroad Coordinator provides the PM and PDT information and feedback from the railroad concerning potential impacts of the highway on existing railroads. The Railroad Coordinator helps obtain necessary approvals from the railroad company and coordinates with the project letting schedules.

Red Flag

As soon as it is known there will be railroad involvement on a project, the PM should document it in the project database system. This can be done by adding Railroad Involvement to the Project Concerns area, notifying the Railroad Coordinator of railroad involvement on a project.

A railroad’s location and topography can normally be obtained from regular roadway project mapping. When the railroad’s location is critical, additional survey data may be needed (e.g., if drainage is diverted toward the railroad ROW, supplemental data may be needed through the impacted area). To index the railroad to the roadway project mapping, the distance to the nearest railroad milepost on each side of the highway centerline must be measured and the information on the mileposts recorded. Be aware that railroad companies may require special permits to enter their property for ground surveying. In some cases, KYTC surveyors may have to be escorted by railroad personnel while on railroad property.

Railroad companies have clearance requirements for the construction of permanent or temporary facilities that encroach on or cross the railroad ROW (e.g., road facilities to maintain traffic flow during construction). A standard vertical clearance of 23 feet must be provided. Vertical clearance is measured from the top of the high rail to the lowest point of the structure in the horizontal clearance area of the railroad. The railroad company establishes horizontal clearance requirements from the centerline of track to the face of a pier, abutment, or other obstacle. Contact the Division of Structural Design for exact clearance requirement information, which can be factored into the study of preliminary roadway alternatives.

All land parcels within the railroad ROW needed for highway construction are to be taken as either permanent or temporary easements. Descriptions must be tied to both highway and railroad stationing.

Highway projects with railroad involvement carry additional costs. To ensure these costs are accounted for in and covered by highway project funding, the PM should request a cost estimate from the Railroad Coordinator for providing railroad-related activities and coordination (e.g., preliminary engineering, final engineering, administration, construction management, flagging).

Analysis of current and forecasted future traffic conditions is a critical input into the project development process. Traffic data and traffic forecasting are needed to determine the nature, physical characteristics, and extent of a proposed project. Traffic data exert a major influence on a project’s Purpose and Need statement (e.g., high average daily traffic may result in a project purpose of addressing capacity and mobility).

Traffic forecasting aims to produce the best possible estimates of present and projected traffic to understand a project’s effects on the overall transportation network. The type and complexity of a proposed project dictate the level of detail required of traffic data to adequately forecast future traffic. In general, more robust analysis is required for roadway capacity expansions. Small projects and spot improvements have less complex requirements.

Major construction or reconstruction projects should be designed to accommodate (at minimum) 20-year forecasted traffic volumes. For 20-year traffic volumes, the design year is 20 years from the estimated base year — the year in which a project is anticipated to open for traffic use.

Present-day traffic volumes are used during the design of smaller projects (e.g., restorations), spot improvements, and bridge replacements. Rehabilitation projects also use present-day traffic volumes except for their pavement design, which considers projected volumes and loads. If after reviewing existing traffic information the PM decides additional traffic information is needed, they should submit a request to the Division of Planning.

Red Flag

If project construction is delayed, forecasted traffic volumes may need to be updated. When this occurs, the PM should discuss the traffic forecasts with the Division of Planning and/or FHWA to determine if the traffic volumes need revisions. For off-schedule projects (i.e., those projects that have been significantly delayed and not made it to letting) the FHWA may ask KYTC to develop updated traffic volume forecasts to verify the project’s Purpose and Need are still applicable for the revised context.

A key traffic consideration for intersection design is vehicle turning movement counts. These data are a controlling factor when making decisions related to several aspects of an intersection design (e.g., type of intersection, whether auxiliary lanes are needed for left- and/or right-turning movements, geometric dimensions of lanes and the intersection, and selection of traffic control devices).

Intersection geometric design is also significantly influenced by the types of vehicles using a facility. Turning movement counts help the PDT select the design vehicle. KYTC uses design vehicle classifications described in American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) policy.

Vehicle turning movements at a proposed intersection can be determined from origin-destination studies, or from known travel demands. Future traffic at a proposed development (e.g., neighborhood, business establishment, school) can be calculated if the type and size of the development is known.

There are several options for completing turning movement counts. The Division of Planning can perform traffic count studies when needed. For these cases, the PM should submit a request for turning movement counts. The PM can also request District-level Design staff or assign the consultant team to complete turning movement counts.

For large‐scale, federally funded projects, an environmental overview (EO) is created in the early stages of project development. These overviews are a preliminary assessment of possible environmental impacts caused by a project and as such require field evaluation. The scope of field evaluations depends on project complexity, and range from windshield surveys (typical) to full environmental investigations (rare).

An EO may consist of one comprehensive document or individual reports, with each report detailing a specific area of environmental subject matter. It may address the full range of environmental disciplines covered under NEPA — pursuant to FHWA implementation — or it may focus on specific project elements necessary to address requirements stipulated by other involved federal agencies, such as U.S. Army Corp of Engineers (USACE), U.S. Coast Guard (USCG), and Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA).

An EO must include a discussion of archival data collected from various sources. Usually, little fieldwork other than a windshield survey of the project area is necessary to verify existing data and conditions. As a common practice, the PDT determines the format and content of the EO during scoping or negotiation activities with the consultant.

Side Note

Conducting an EO within the project area is recommended before studying alternative corridor and/or roadway alignments.

For larger or controversial projects — those which require an environmental document type of FONSI or EIS — it is necessary to have a public meeting as soon as possible in the project development process to address the Purpose and Need statement. (Projects approved as a CE may also use a public meeting). Public Meeting #1 is typically an informal public kickoff for the project. The purpose of this meeting is to gather information, determine community support for the project, and understand community issues and its goals for the project.

Stakeholder engagement helps the PM and PDT develop a better understanding of conditions in the project area. Stakeholder groups may include members with a variety of backgrounds (e.g., local officials, emergency services, school transportation and/or administration, utility owners impacted). It is useful to tailor the composition of stakeholder groups to the needs and context of each project. Often the stakeholder groups continue to meet periodically to receive updates and project-related information from the PDT. If more direct involvement with the PDT is needed, the PDT may engage a subset of the stakeholder group through a focus group.

For more information on public meetings, see the Highway Design Guidance Manual (HD-600).

When KYTC identifies a Purpose and Need for a highway project but lacks a strong preference on proposed solutions (e.g., a new corridor roadway), a Blank Slate Meeting may be a good first step for public involvement. Blank Slate Meetings are held when there has been little study done or work completed on a project, and thus the plan for potential design alternatives remains a blank slate. They may be open to the public or invitation-only events for designated stakeholders/ citizen advisory groups. These meetings should typically occur as early in the preliminary design and environmental process as practicable.

At the Blank Slate Meeting, the PDT exhibits aerial photos of the project area/corridor, showing existing planimetric mapping with no proposed roadway elements. An environmental footprint map indicating sensitive areas can be presented if database and/or windshield investigations have already been conducted. Displays may show other available data (e.g., traffic counts, crash data, utilities). Possible roadway alternatives and geometric improvements are not shown.

During the meeting, KYTC officials introduce the project’s purpose to attendees and state that no referred alternatives have been identified. They communicate that the meeting’s purpose is to better understand the project context. Officials solicit feedback from attendees, with a focus on their biggest concerns about the project. A member of the PDT should take notes. Attendees have the opportunity to write their concerns on the mapping or on surveys. They will also be asked to describe what steps KYTC can take, if any, to alleviate their concerns, (e.g., what project improvements they think are needed). Dialogue with attendees can help identify resources, issues, or concerns important to the community that may require consideration during design.

Blank Slate Meetings have three intended outcomes:

1. Educate the Public – The PM and PDT should inform the public and stakeholders about the project development process. Many attendees will likely be experiencing impacts from a highway project for the first time, and it is critical to describe to them the project development process. The public is more likely to trust the outcome if they understand the process and see that all impacts have been weighed against one another before a decision is made.

2. Relationship Building – Building rapport between the PDT and members of the public is crucial. KYTC and the PDT are openly soliciting public opinions during a period when there are no preferred design alternatives. A PM should seriously consider this type of meeting if: 1) they have a sense the public is wary of the project, 2) there is an issue with the project of longstanding concern, or 3) the media and/or public officials are involved.

3. Fact Finding and Discovery – The PDT should gather important information about the existing context, much of which cannot be found from database searches (e.g., family cemeteries, undocumented traffic accident locations).

For more information on public meetings, see the Highway Design Guidance Manual (HD-600).

At the beginning of project development, it is of great benefit to have information about the project context before evaluating proposed alignments. Information may be acquired through a Red Flag Abbreviated Planning Study (Red Flag Study), the goal of which is to identify early on significant existing features on a project. If these features remain unknown and are impacted by the project, KYTC may incur expenses and/or delays that could have been prevented.

A Red Flag Study is generally a bound document that collates as much database information as possible (e.g., HIS, environmental, economic, safety) and adds an enhanced layer of SME knowledge. It includes more information than other planning reports, (e.g., DNA studies), since it contains professional input from SMEs. For example, historians will do a windshield survey of the project corridor and make a list of potentially historic-eligible properties. Biologists will identify wetlands or sensitive streams. ROW Agents will evaluate properties. Utility Coordinators will catalog complex utility facilities. SME information is compiled into a list of existing human and natural environment issues, many of which may be prominent features that will significantly influence or control project design. If these features are known as roadway design begins and preliminary alternatives are created, scope of impacts on these features can be considered and — hopefully — avoided completely. The Red Flag Study can potentially save time and effort as it exposes items which, if impacted, will delay schedules and increase costs.

The PM requests the Red Flag Study of PDT members. The PM and PDT should jointly plan the study’s focus, which may be as broad or narrow as needed. For example, a Red Flag Study could focus solely on environmental red flags. Or in addition to the environmental overview, it could include traffic information and potential utility or ROW conflicts. The Red Flag Study is helpful on projects that have not had a planning phase, particularly where a range of potential alternatives need to be honed and prioritized according to need and cost. The studies might also be helpful on projects with multiple designers and when a larger project team needs to be aware of the same design constraints. Information collected during a Red Flag Study becomes a part of the project record, helping establish the basis and reasoning for alignment development.

Side Note

The red flag concept may be applied to any project regardless of size or complexity. For smaller projects, Red Flag Study documentation or deliverables are adjusted commensurate with the level of the project. For example, a simple bridge replacement project will likely not need a large bound document — red flag information can be communicated to the PDT in meetings or via a simple email. Red flag work is valuable on any size project, and it should facilitate work on project planning, development, and design.

Time Management for Highway Project Development Knowledge Book:

Access the complete Knowledge Book here: Time Management Knowledge Book

Next Article: Project Cost Estimation and Management

Previous Article: Build Your Team