Search for articles or browse our knowledge portal by topic.

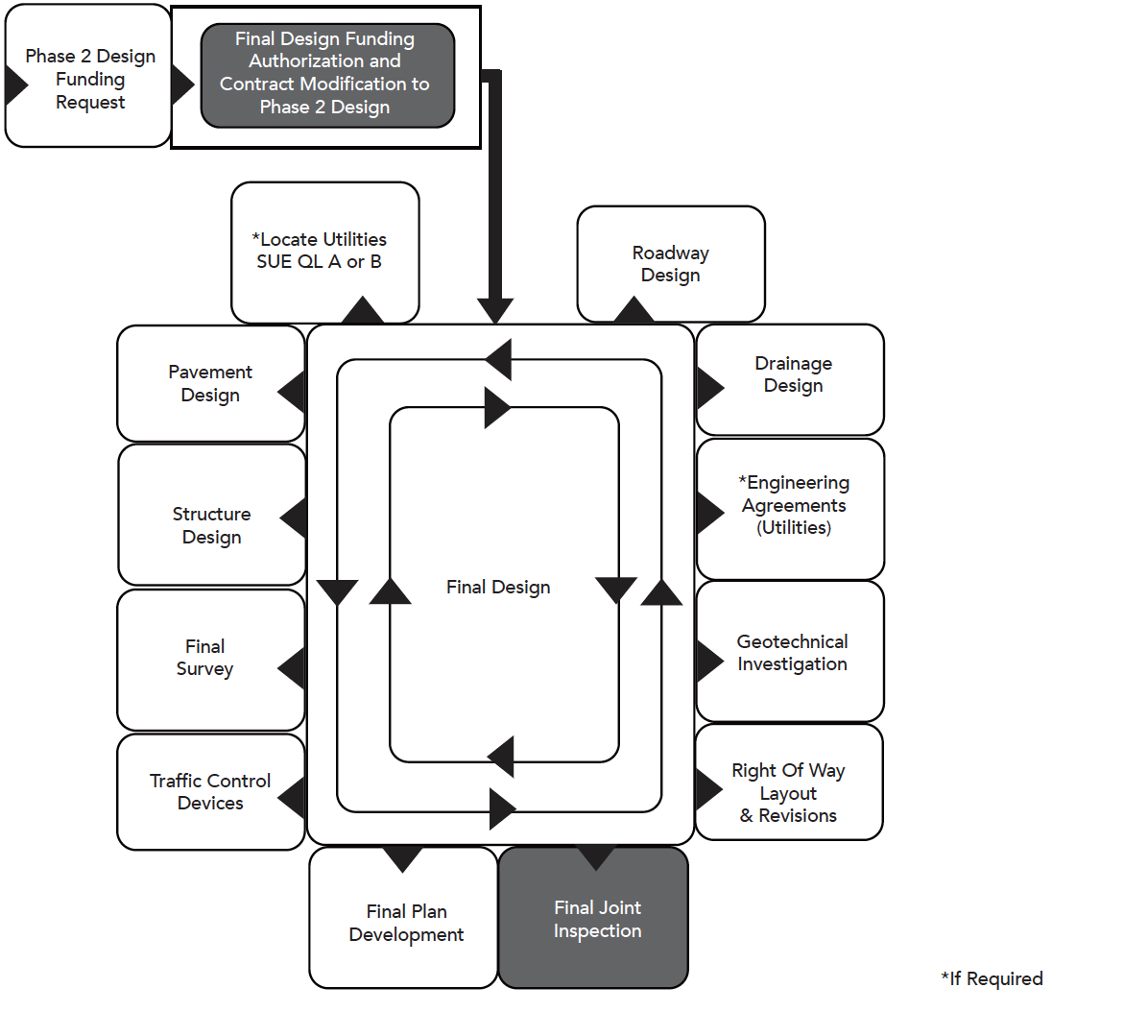

Final Design Phase

Once an alternative is selected and the transportation decision is documented, the project moves into the Final Design Phase (i.e., Phase 2). The final design must preserve resolutions to project-specific issues or special circumstances identified in preliminary design. Details prepared for the selected alternative in the Final Design Phase are used to develop plans for ROW acquisition, utility relocation, and construction.

On larger projects, project development is commonly broken into two phases. Larger projects require greater project definition through the Preliminary Engineering Phase to understand the type and amount of work needed in the Final Design Phase. For these projects, the PDM initially requests sufficient funding to complete preliminary engineering and environmental work. After a transportation decision is made and adequately documented, the PDM requests additional funding for the final design. Phase 2 requests are dealt with in the same manner as initial Design Funding Authorizations.

Red Flag

Design Funding Authorization may take several months once the initial request is submitted, especially at the beginning of a new biennium and new Highway Plan. The Central Office’s organizational planning prioritizes projects based on risk, funding, and KYTC’s strategic plan. When multiple Design Funding Requests are submitted, the PDM should communicate the projects’ needs and the risks to the Central Office to assist with project prioritization. For time-sensitive projects (e.g., those whose on-time delivery are placed at risk if an activity on the critical path does not begin on time), the PM should communicate to Program Management the need for an expedited Design Funding Authorization process. FHWA must approve funding requests on Federal-aid projects, which adds review time.

Sometimes FHWA requires a final, approved NEPA document before it will authorize a PR-1 form to allocate additional federal funds for Phase 2 design.

Milestone with Federal Approval

When additional phases of work are added to the scope of a project on which consultant services are used for project development, the contract must be modified and the schedule adjusted. The Division of Professional Services assists the PM with contract modifications. A contract modification is negotiated using the same procedure as the original contract.

The Division of Professional Services webpage contains helpful tools and guidance, including the Professional Services Guidance Manual. See also the Highway Design Guidance Manual (HD-205).

Red Flag

Contract modifications go through a review process that is similar to the review process used for the original contract. The Division of Professional Services finalizes the contract and sends it through KYTC’s approval process. When the Division of Professional Services receives eMARS approval (indicating the contract has been automatically filed with the LRC Government Contract Review Committee) the Division sends a notice to proceed and approval for payment to the firm, which indicates it may begin work and bill for services.

Detailed plans and documents needed for ROW acquisition, utility relocation, permitting, and construction of the selected alternative are produced during final design (i.e., Phase 2 design). Resolutions for project-specific issues or special circumstances identified in the Preliminary Design Phase must be reflected in the final design.

When activities in one subject-matter area influence work in another during final design, an iterative approach should be adopted during the revision process. Work between subject-matter areas can and should overlap. During this phase, the PM relies on the Critical Path Schedule to target work situated on the critical path and to identify strategies to keep the project moving forward.

Red Flag

The PM benefits from having an organized system to track and retain files. Throughout project development — but especially during the final design, ROW, and utility phases — updates are made frequently and organizing materials in a straightforward manner is critical.

Composition of the PDT might not remain constant from Preliminary Design to Final Design. When changes to the project team happen, the group needs the PM and/or other PDT members with a history of working on the project to help adjust and coordinate their work effectively. Sometimes the composition of the PDT changes as members depart from the team. To preserve momentum during project development in the event of staff turnover, it is imperative to maintain exhaustive yet clear project documentation. This is non-optional — it must be done.

As details are refined throughout the roadway design plans, the PDT should gain a clearer understanding of the design’s impact on existing utility facilities. It may be necessary to investigate at a higher quality level the facilities that could be in conflict with proposed roadway construction (including temporary maintenance of traffic) to determine how extensive the impacts will be. Higher quality level subsurface utility data, when collected early in the final design phase, can help the PDT determine whether utility impacts can be avoided or minimized and facilitate ongoing utility coordination with facility owners.

SUE Quality Level A or B may be thought of as an activity performed during the utility phase, unless the potential impact is sufficient for the PDT to potentially consider a redesign. Examples of utilities that may prompt a redesign include large gas transmission lines, water mains, buried fiber optic cable, and other facilities whose relocation will result in costs or delays disproportionately large compared to the overall project budget and schedule.

Even if a utility relocation is not reimbursable (i.e., direct costs will not impact the project budget), the PDT may elect to avoid it if the relocation work significantly impacts the overall project schedule.

The PM has options to acquire Quality Level A detail. Using a letter agreement for statewide surveying services may be faster than waiting for a modification to the original consultant contract.

A proposed drainage plan for the selected alternative includes culverts and headwalls, inlets and storm sewers, bridges, temporary drainage, and project-specific drainage needs. Proposed drainage plans must contain economical and hydraulically feasible solutions that comply with KYTC’s policies, specifications, and standards.

Once the drainage design meets the PDT’s expectations, all relevant information is placed in a drainage folder. The folder format facilitates the organization of documents as well as the review process. The PM provides the drainage folder to the Central Office. Drainage folders are required on all projects that:

• Contain major drainage structures, including structures used to transport water directly through, or which delay the flow of water into or away from, the highway system; or

• Include extensions of existing structures or improvements to those structures or drainage systems.

The Division of Highway Design uses two drainage folders: preliminary and final. Typically, preliminary drainage folders are not required unless bridges, bridge-sized culverts, storm sewers, or major channel changes are among the drainage features. A third folder — the advance situation folder — is primarily used by the Division of Structural Design. The Highway Design Guidance Manual (HD-204.12 and HD 204.19), Highway Design Drainage Manual (DR-300), and Division of Structural Design Guidance Manual (SD-200) contain detailed instructions on procedure and format.

A Drainage Inspection Meeting — which the PM is responsible for scheduling — is held for each project. It is often combined with the Final Joint Inspection Meeting, with comments on drainage design being incorporated into the meeting minutes. If a project or the drainage design are complex, a separate Drainage Inspection Meeting may be held. Whether the Drainage Inspection Meeting is combined with the Final Joint Inspection meeting or held independently, its purpose is to review material submitted in the preliminary folder and let SMEs ask questions about elements of the submittal they are unclear on.

A separate drainage inspection report is prepared when a Drainage Inspection Meeting is held, or if the PM deems it appropriate. Regardless of how minutes are documented, discussions on drainage design are placed in the drainage inspection report. This report summarizes written comments from SMEs on the drainage design as well as the responses from the PM and/or drainage designer. It also documents that all personnel concur with the final drainage design (including modifications made based on SME reviews of the initial design). When project plans call for using larger drainage designs and features, the drainage inspection report recommends location, span arrangement, abutment type, and the sounding layout for drainage structures, piers, and abutments. The drainage report also documents if scour analysis is needed, which is determined during the geotechnical investigation. The PM must ensure the report includes the Central Office Drainage Engineer’s endorsement of the Drainage Inspection Meeting minutes and comments.

The final drainage folder includes recommendations from the review process and serves as the permanent record of the project drainage plan. It contains all of the required information to support the selection of drainage items proposed in plans, and it documents final resolution(s) of drainage inspection comments. In the event of flooding and subsequent lawsuits by plaintiffs whose properties were damaged by high water, the final drainage folder contains the materials KYTC will cite as evidence to justify and defend its decision making. Variations of current practices and standards incorporated into the drainage plan are fully documented in the final drainage folder.

Red Flag

The advance situation folder is treated as an order form that instructs the Division of Structural Design to either begin structure design or to direct a consultant to begin this work on KYTC’s behalf. The advance situation folder should contain explicit requirements identified by the PDM and PDT project team.

The installation of drainage structures can present significant challenges related to constructability and maintenance of traffic (MOT). Of particular concern are pipe culverts with either little cover or extraordinarily deep cover heights. The PM may consult with staff possessing construction expertise to identify strategies that minimize cost and project delays during later work phases.

Red Flag

Many local governments have ordinances, codes, guidelines, or other requirements that influence roadway drainage design for projects in their jurisdiction. KYTC pursues additional coordination with local governments that have specific drainage criteria, including the Municipally Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4), Louisville and Jefferson County Metropolitan Sewer District (MSD), and Lexington- Fayette Urban County Government (LFUCG.) Consult the Drainage Guidance Manual and drainage staff for assistance.

Designing the pavement structure to support the traffic load and distribute it to the roadbed requires the PDT to draw on resources from the Division of Planning, the Division of Structural Design’s Geotechnical Branch, and the Pavement Branch of the Division of Highway Design. With the support of these KYTC staff, the PDT documents the project-specific conditions and decisions made in the pavement design process.

The Pavement Branch develops pavement designs and engineering analyses for all projects on the National Highway System (NHS) and projects having at least 20 million equivalent single axle loads (ESALs). For other projects, the PDT performs all project-related design activities including pavement design, engineering analysis, and documentation. Specific submittal and approval responsibilities are listed in the Highway Design Guidance Manual (HD-1001.2). Pavement Branch staff provide technical assistance, review and advice, training, and support. Consult the Pavement Design Guide when preparing pavement designs for new construction or full-depth reconstruction projects.

Kentucky uses AASHTO’s mechanistic empirical (ME) pavement design process and AASHTOWare’s Pavement ME software. For most new and reconstructed pavements in Kentucky, designers use Pavement ME. A 20-year design life is recommended if Pavement ME is used to develop the structural design. Pavement Branch staff assist the PDT in tailoring solutions to project-specific conditions.

Optimal pavement designs adapted to the conditions and characteristics of each project location depend on engineering factors, including:

• Traffic

– Consider both total volume and the percentage of truck traffic when selecting pavement type.

• Subgrade Characteristics

– The load-carrying capacity of a native soil is of utmost importance in pavement performance. The Geotechnical Branch offers guidance and makes recommendations with respect to subgrade stabilization.

• Construction

– Speed of construction, maintenance of traffic stages, anticipated future widening, and ease of replacement may influence the selection of pavement type.

• Cost

– Initial construction costs, the cost of subsequent stages or corrective work, anticipated life, maintenance costs, and costs to road users during periods of reconstruction or maintenance are all important considerations.

The PDT initially selects hot mix asphalt (HMA) bound material or Portland Cement Concrete (PCC) pavement (flexible or rigid). Alternate Pavement Type Bidding (AD/AB) procedures may generate project savings if one pavement type does not hold a clear advantage over another.

Red Flag

A Special Note is used in plan documents to record the use of nonstandard and new materials, equipment, or testing prescribed for a project. Many examples of Special Notes are available on the Pavement Branch’s web pages on the Division of Design website. These include Special Notes for Non-Tracking Tack Coat, Inlaid Pavement Markers, or Asphalt Pavement Ride Quality (Rideability.)

To avoid delay in finalizing a pavement design, traffic data (from the Division of Traffic) and soil characteristics and the California Bearing Ratio (CBR) (from Geotechnical staff) should be requested as early as possible in project development.

An excessive number of pavement mix designs can increase construction bid pricing and unnecessarily complicate general bookkeeping. The PDT should review mix requirements and consolidate them as much as possible, using input from Pavement Branch and Materials staff.

Final Roadway Design addresses a collection of project-specific topics. The outcome of Final Roadway Design is a set of plans, profile sheets, cross sections, and the necessary detail sheets. During final design — if not earlier — roadway design staff engage in and complete work on numerous topics. Examples of topics on which work is completed include the following:

-

- Intersections,

- Roadside safety and guardrail design,

- Item quantity takeoff measurements for the general summary, pavement summary, and drainage summary (bid item quantities and types),

- Final earthwork volume measurements according to each material classification,

- Construction estimate,

- Erosion control plan details,

- Construction notes,

- Traffic control plan (TCP),

- Traffic Management Plan (TMP)(see HD-206.3), including the PIP,

- Signing and pavement markings/striping plan,

- Pedestrian and/or bicycle facilities design,

- Proposed ROW and easements,

- Deed descriptions for proposed ROW,

- Finalization of plan deliverables (including electronic files).

Red Flag

A Value Engineering Review may be required. Other specialty reviews are available (e.g., a Constructability Review). Refer to Highway Design Guidance Manual (HD-203.7.4, HD-204.23) for details.

Building the roadway and supporting structures is the primary goal of most highway projects. As such, the road designer’s plans are often the focal point of the project’s construction documents. The PM and road designer must communicate with the other PDT members to convey intent of the design (especially as new details are derived). The converse is also true: as the SME’s team members make decisions and discover new details about the project, they need to convey this information back to the PM and the road designer, especially if it affects the road design and/or needs to be included in the plans.

During preliminary line and grade inspection, the project team considers and discusses potential traffic control measures for each alternative and the inspection report summarizes the discussion. The designer should develop detailed construction phasing plans for the preferred alternative so they can be reviewed at the joint inspection. Traffic control measures should be developed and included as drawings and notes on temporary traffic control sheets in the plans.

For projects designed by Department of Highways staff, the PM furnishes the Division of Structural Design with all necessary data for analysis and design (including the Advance Situation Survey and Advance Drainage Folder). When a consultant prepares designs for bridges, box culverts, tunnel liners, retaining walls, and noise barriers, they are submitted to the Division of Structural Design for review and approval. The review process has five phases:

1) Advance Situation Survey

2) Preliminary Plans, Stage 1

3) Preliminary Plans, Stage 2 (if required)

4) Final Plans, Stage 1

5) Final Plans, Stage 2

Detailed format and content requirements for the submittal are described in the Structure Design Guidance Manual, Drainage Guidance Manual, and Highway Design Guidance Manual.

The purpose of a PM’s review of early-stage and final-structure plans is to ensure a structure’s design aligns with the project’s intent and does not conflict with other project details (e.g., utilities, MOT, environmental concerns)

The Geotechnical Report should be completed prior to the Advance Folder submittal, otherwise the final structure design will be delayed due to the time needed to finish the geotechnical work.

For bridges with wall-type abutments, a spill-through–type structure is generally more economical than a short-span structure with tall abutments. The selection of bridge type should be coordinated by the PM in concert with Division of Structural Design.

In many cases, the demolition and disposal of existing structures is addressed within the Standard Specifications. But in other cases, special demolition instructions may be needed, such as when the partial demolition of an existing structure carrying traffic is necessary.

Project details that complicate structure design (and the other phases project development) include:

-

- Curved bridges

- Phased construction

- Steel bridges

- Railroad overpass or underpasses

Red Flag

Bridges located on curved alignments (horizontally and vertically) cost more to design and construct than bridges on straight alignments. If a structure cannot be located outside a curved roadway segment, the next best option is to keep the bridge outside of pavement transitions. When it seems that a bridge alignment may need to be on a curved alignment, the PM and road designer should coordinate early with the bridge designer to ascertain structure options and decide what the preferred bridge structure would be.

If permits or approvals from other agencies are required (e.g., USCG, FHWA), or the structure is complex, the amount of time that should be allocated for project development is significantly longer.

Engineering Service Agreements are keep-cost agreements that KYTC uses to reimburse utility company staff or an approved consultant for relocation engineering and administrative work. These agreements may be established for engineering, accounting, legal, appraising, or consulting services. They can be used for any of the following reasons:

-

- The utility company requires the immediate ability to invoice only the engineering work.

- Utility relocation will be included in the highway contract, and the utility company will not be directly reimbursed for construction costs.

- The Cabinet has determined that Utility Relocation Engineering should begin before U Phase Funding is available.

As noted in the entry, Project Time Management Article 4 Data Gathering, Sections 3, 4, and 5: Identify and Contact Involved Utility Companies and Locate Utilities, the preliminary utility engineering design relocation may be initiated before U Phase Funding authorization. Initiation may occur as early as the start of roadway design. If the work is eligible for reimbursement, D Phase Funds are used.

Early initiation is encouraged on the following project types:

-

- Extensive utility work is needed and cannot be completed without early utility engineering.

- Adhering to the project schedule is not possible without early utility engineering, and the letting date must be maintained.

- The project includes complex utility relocations that require more extensive and time-consuming coordination efforts (e.g., impacts to gas transmission lines).

- Utility easements must be procured, and preliminary engineering is required to identify the easement.

When engineering agreements are used, Preliminary Engineering (relocation design for the utility) is reimbursed by a separate agreement using a funding source that differs from what is used for utility relocation construction. Relocation construction may be reimbursed under a typical keep-cost or lump-sum relocation agreement.

Red Flag

Only engineering-related work can use D phase funding. Absolutely no construction may be paid for with D Phase funding.

KYTC approval and authorization of engineering services (whether utility company personnel or their consultant) is applicable only to utility companies authorized to receive compensation for relocation work.

The Final Survey Report records project details and is submitted to the PDM. This report generally includes the following information:

-

- Project name and identification, including:

- County, Route, Mile Post, or Project Identification

- Survey date, limits, and purpose

- A scaled map (e.g., KML file) of the project area that shows all primary and supplemental (horizontal & vertical) control monumentation established along with appropriate designation

- Dated signature and seal of the Kentucky Professional Land Surveyor in charge

- Closures of all traverses

- Document all pertinent information of all control on Control Monument Data Sheets

- Project name and identification, including:

Refer to the Highway Design Guidance Manual for more information.

Survey pickup will be necessary at multiple times throughout final design as the designers encounter details that are new or require confirmation. (The PM is encouraged to collect survey needs and strategically order the survey as efficiently as possible). Examples of this type of small-scale survey work include the identification of a new building or feature, a disputed property boundary between two parcels, a developing slide, or septic lines. Having accurate knowledge of where existing structures are located and their boundaries is particularly important to the design process.

Red Flag

Unless the project scope explicitly states otherwise, a survey report will not be accepted from a non-KYTC source unless it is signed, dated, and stamped by a Kentucky Professional Land Surveyor certifying the accuracy of the submitted report and verifying the accuracy of all control monuments established for the Department of Highways.

If a project is temporarily shelved or otherwise delayed, surveys of existing topography and property lines may become outdated and inaccurate. If so, additional time and resources will be needed to update the existing digital terrain model (DTM).

Additional survey pickup may be needed during ROW acquisition, because property owners often provide new or more accurate information than was previously available.

Through consultation with the Geotechnical Branch, the PDM determines the level of geotechnical investigation required for the project. This level of effort ranges from advisory to a full-scale geotechnical analysis, with fieldwork, lab work, and reports for roadway, structures, or both. Traditionally, the investigation begins after the Preliminary Line and Grade Meeting has been held and the alignment selection has been made. However, geotechnical information sought and received earlier in the project development process is invaluable for the PDT’s decision making. For example, with early geotechnical recommendations for cut and fill slopes, much more accurate estimates of the disturbed area and the amount of ROW needed can be produced.

The Highway Design Guidance Manual, Drainage Guidance Manual, Geotechnical Guidance Manual, and Structures Manual all contain information on the level of geotechnical investigation appropriate for a given project feature. Increased geotechnical investigation is needed where springs, landslides, mines, karst, faulted strata, acidic shale, mineral deposits, or other topographic or subsurface features are present.

More extensive geotechnical field data collection and analysis are required for large drainage structures than for smaller structures. A large drainage structure is one that meets one or more of the following criteria:

-

- All bridges

- Culvert pipes with a diameter (or equivalent) greater than or equal to 54”

- Culvert pipes with improved inlets

- All cast in place box culverts

- All precast or metal box culverts 4’ span x 4’ rise or larger

- All bottomless (3-sided) structures

Final plan development relies heavily on geotechnical report recommendations. The Geotechnical Branch provides the following sheets for inclusion in the roadway plan set: Geotechnical Notes Sheets, Geotechnical Symbols Sheets, and Soil Profile Sheets. Soil profile sheets are developed at a scale appropriate for the project. The soil profile can be used to establish cut and fill slopes. CBR values can be used to develop the pavement design, cut and embankment stability sections, and rock refill. The designer determines the quantities of rock available from roadway excavation and the quantity needed for rock roadbed, embankment, and rip rap using information from the geotechnical report. Embankment foundations and/or transverse (profile) benches, granular embankment, or a proving period may be needed.

Side Note

The scope of geotechnical investigations is often minimized on projects selected for expedited delivery to reduce costs and maintain the desired schedule. When evaluating how much risk will be assumed by omitting or limiting the scope of geotechnical investigations, the PM should work with a geotechnical SME to prepare a geotechnical action plan with acceptable risk levels.

Red Flag

When performing early geotechnical field investigations, analyze the environmental setting to verify that no sensitive features (e.g., archaeology, forested habitat, special use stream or wetland) will be adversely impacted by geotechnical work (e.g., drilling). The PM must decide if an environmental overview should be conducted prior to geotechnical field investigations.

The Geotechnical Branch’s online database houses the results of completed KYTC geotechnical investigations. Additional geotechnical mapping and information may also be obtained from the Geotechnical Branch. The Geotechnical Branch’s online database is located at: http://kgs.uky.edu/kgsmap/kytcLinks.asp

To retain flexibility in project work tasks and keep a project moving forward, a PM may want to consider initiating geotechnical fieldwork for the roadway investigation separately from the geotechnical fieldwork for the structures investigation.

Karst terrain (including sinkholes, closed drainage basins, sinking streams, caves, and similar geohydrological features) requires additional investigation and analysis during design. Stringent guidelines for drainage design and construction are in place and must be adhered to if sinkholes will be used for drainage.

Potentially adverse pH conditions in the surrounding soils and geology should be evaluated. Elevated acidity can result from strip mining or other actions that expose acid-producing soils, acid shale seams, or other acid-producing formations. Additional requirements during design and construction should be expected where these conditions are present.

A common source of plan error is omitting recommended quantities from the geotechnical report. For example, it may be helpful for the report to list where rock and fabric are recommended to deal with the presence of saturated soil. Omitting these quantities from the plan quantities can result in overruns or change orders.

Traffic control devices regulate, inform, warn, or guide drivers. Examples of traffic control devices include signing, pavement markings, electrical traffic control devices (including traffic signals), and lighting. The PM is responsible for identifying and including appropriate traffic device plans in the total plan set.

Once the PM identifies project locations that may require signal, signing, and/or lighting plans, they notify the District Traffic Engineer and Central Office Traffic Operations. (To facilitate this process, the PM should notify the District Traffic Engineer of project meetings and inspections as early in the process as feasible.) The District Traffic Engineer will send a written request and provide appropriate supporting information to Central Office Traffic Operations.

The Division of Traffic Operations provides oversight when a consultant is hired to design signing, signals, or lighting devices. Oversight takes place during plan development and through a review of final plan details. Alternatively, Traffic Operations may design devices in-house and coordinate project details with the PM. Road projects generally include the design and installation of one or more of the following devices:

• Signs: Plans are prepared for new sign installations for interstates, parkways, and other high-volume, limited-access roads that include interchanges. See the Traffic Operations Guidance Manual (TO-400) and Highway Design Guidance Manual (HD-1201.2).

• Pavement Markings & Delineation: Like signs, pavement marking plans are prepared for interstates, parkways, and other high-volume, limited-access roads that include interchanges. See the Traffic Operations Guidance Manual (TO-500) and MUTCD.

• Electrical Traffic Control Devices: The PDT may choose to modify existing electrical devices or install new electrical devices on a project (e.g., traffic signals, advance warning flashers, railroad-warning system, flashing beacons, school flashers). When this occurs, District Traffic Operations forwards the recommendation to Central Office Division of Traffic Operations (on the PM’s behalf). It contains roadway plan details, traffic counts, traffic projections, and crash history. See the Highway Design Guidance Manual (HD-902) and Traffic Operations Guidance Manual (TO-600) for more information.

• Lighting (e.g., conventional light poles, high-mast lighting): The process for requesting lighting designs and plans is described in the Highway Design Guidance Manual (HD-902.7) and Traffic Operations Guidance Manual (TO-701 through TO-716).

• Miscellaneous: The PM should confer with the Division of Traffic Operations when making decisions about rumble strips, runaway truck ramps, and work zone traffic control (see TO–801 through TO-803).

In 2012, the Division of Highway Design (No. 03-12) and Division of Traffic Operations (No. 01-12) issued a joint memo that explains procedures for developing plans for electrical devices as part of a roadway design project. Plans must be developed in accordance with:

-

- Kentucky Transportation Cabinet (KYTC) CAD Standards,

- Kentucky Standard Specifications for Road and Bridge Construction,

- Traffic Operations Guidance Manual,

- Highway Design Guidance Manual,

- Division of Traffic Operations’ Roadway Lighting Standard Detail Sheets,

- National Electrical Code,

- National Electrical Safety Code,

- MUTCD, and

- AASHTO’s Roadway Lighting Design Guide.

Red Flag

To avoid conflicts (e.g., expensive utility impacts, time-consuming ROW purchases), the PM must coordinate the design of signs, signals, and lighting devices with all other design processes. Under no circumstances should this be postponed it until the project letting nears.

All sign supports located in the clear zone must have a breakaway design or be protected by crashworthy barriers. When struck by a vehicle, a breakaway sign support either separates from the base or yields, allowing the vehicle to run over it. When possible, coordinate sign placement with the barrier systems that will be used on the project. The PM coordinates with the Division of Structural Design on the structural design of sign supports.

The PDT considers numerous factors when establishing limits for the proposed ROW. The extent of ROW must be sufficient to accommodate the construction and maintenance of the new roadway and structures. Access control type(s) affects new ROW limits as well as the location of entrances or approach tie-ins. Deed research undertaken as part of survey work clarifies the existing ROW and property boundaries and is used to identify prior easements or rights (e.g., mineral rights or access) that must be addressed during ROW acquisition. It may be appropriate to acquire permanent fee-simple ROW, permanent easements, temporary easements, or some combination of these.

Whenever ROW plans are modified, a Right-of-Way Revision Sheet is added to the ROW plans. It is inserted directly after the layout sheet and numbered R1a; see the CAD Standards for Highway Plans. Each time a revision is processed, the Right-of-Way Revision Sheet should be updated electronically, reprinted, and inserted into the plans. For some projects, the Director of Division of Right of Way and Utilities may adopt an informal version of this revision process. Regardless of the method used, it is important to meticulously track all changes. The District Right of Way Supervisor keeps the Director of the Division of Right of Way and Utilities apprised of the status of the project plans and deeds.

Red Flag

For parcels that proceed to condemnation, the PM must identify and then preserve the plan version used at the time the suit was filed even if ROW revisions occur adjacent to the parcel being litigated. Legal staff also require exhibits or prints; those files must be similarly preserved.

Adequate temporary easement must be provided around improvements if they will be demolished after ROW acquisition. Examples include pond dams and buildings.

Adequate ROW must be provided to maintain traffic and perform construction activities even if doing so produces a larger footprint than what is needed for the final roadway.

Contract plan sets are the highway plans awarded through the letting process. They are a product of the project development process and consist of the roadway, structures, traffic, and/or utility relocation plans. When contract roadway plans and proposals are submitted to the Division of Highway Design’s Plan Processing Branch, all electronic file submittals must adhere to the standards outlined in the CADD Standards for Highway Plans. These standards have been established to ensure files are put to the best possible use during the review, publication, construction, and archival processes. The standards represent the minimum requirements for the development of highway plans and are available online at: http://transportation.ky.gov/CADD-Standards/Pages/default.aspx

Red Flag

Performing a final comparison of the structure and roadway plans during final plan development is worthwhile, especially for reconstruction projects. For example, if a new structure’s beam arrangement conflicts with MOT plans for using the existing structure, the project will take longer, the contractor may file a claim and a change order could become necessary. Finding and addressing such issues during design saves time and expense later.

Milestone

During the Final Joint Inspection Meeting the PDT and project-specific SMEs (e.g., environmental, ROW, utilities) review the project design and the proposed contract plans and documents. Construction, maintenance, traffic, structures, and drainage staff may be invited to attend and offer input. The proposed plans are distributed in either electronic or paper (i.e., hard copy) format to attendees prior to the meeting so they can perform a detailed technical review of the project’s design and prepare feedback. This technical review provides reasonable assurance that the project design is complete, accurate, and of high quality.

Another goal of the review is to confirm that the roadway design information found in contract documents will effectively communicate the engineering details, facilitate construction contracting, and help to achieve project construction that is consistent with KYTC requirements and specifications.

All projects should have a Final Joint Inspection Meeting. One is held when the contract plans are approximately 80 percent complete. The plans reflect approved decisions from the DES, as well as all ROW and utility information, including identified relocations, detailed MOT information, and traffic plans. (Proposed construction phasing plans for the preferred alternative should be available for review at the joint inspection; see the Highway Design Guidance Manual (HD-206)). Other Design Review Meetings can be combined with the final inspection (such as a structure review for bridge replacement projects or the drainage inspection). The PM makes the contract plans available to the PDM and the Location Engineer. The Final Joint Inspection Meeting is scheduled to ensure that the PDT has at least two weeks to review the plans. When appropriate, contract plans are made available to the FHWA and city or county. A construction cost estimate detailing biddable quantities is included.

Side Note

As representatives from multiple specialty groups attend the Final Joint Inspection, the meeting can have a large number of attendees. As such, its success hinges on good planning and focused discussions. The PM can take the following steps to ensure a successful Final Joint Inspection Meeting:

- Create and distribute a systematic agenda

- Focus attendees by using a single display for the entire room

- Designate one meeting facilitator who is responsible for keeping discussions moving

- Group agenda topics according to the specialties represented (i.e., team members may wish to attend only the discussions relevant to their expertise.)

Side Note

The DEC (and environmental SMEs) may review plans at the Final Joint Inspection to verify environmental commitments are accurately documented. During the meeting, the PM should remind the PDT of commitments made in the NEPA document. For example, impacts to historic properties should be reviewed and taken into account as ROW plans are generated (a task regularly completed after the Final Joint Inspection). Follow through after the Final Joint Inspection can prevent the erroneous purchase/demolition of an eligible structure. Refer to Design Memo 01-18 for additional guidance.

Red Flag

Under no circumstances should the Final Joint Inspection Meeting be scheduled before the following have been completed: the geotechnical investigation, structure design, pavement design, drainage design, and roadway design.

Final Joint Inspection Meeting attendees should be granted at least two weeks to examine review materials. Schedule the distribution of review materials accordingly.

The Final Joint Inspection meeting minutes are a critical part of the design documentation. These minutes should document most, if not all, of the final design decisions.

Time Management for Highway Project Development Knowledge Book:

Access the complete Knowledge Book here: Time Managment Knowledge Book

Next Article: Right of Way Acquisition

Previous Article: Environmental Approval