Search for articles or browse our knowledge portal by topic.

Project Cost Estimation and Management

Note: The topic of Project Cost Estimation and Management appears in two Knowledge Books.

For a time management perspective, access the Time Management Knowledge Book.

To learn more about the project management process, access the Project Management Guidebook.

The goal of project cost management is to control costs through estimation, budgeting, and continuous monitoring of project expenses. Sound project cost management plays a critical role in helping project managers (PMs) complete projects within approved budgets. First, it is important to distinguish between estimates and budgets and to define their relationship to cost management.

An estimate approximates the amount of funding needed to complete a project. Estimates are generated and revised throughout project development, from planning through letting. A budget represents the funding authorized for project expenditures. It serves as a cost baseline and facilitates program management. Project budgets for capital projects and some asset management projects usually appear in the Six-Year Highway Plan (SYP), a legislative document approved and enacted by the Kentucky General Assembly during its biennial budget process. The SYP is intended to be fiscally balanced, making it critical that projects remain within budget. If a project exceeds its budget, less funding is available for other projects throughout the Commonwealth, potentially resulting in delays. Delayed projects reduce the public’s confidence in the Cabinet’s ability to meet project and program commitments. Robust project cost management processes help to ensure projects stay within budget and on schedule.

1.1 Estimating Project Costs

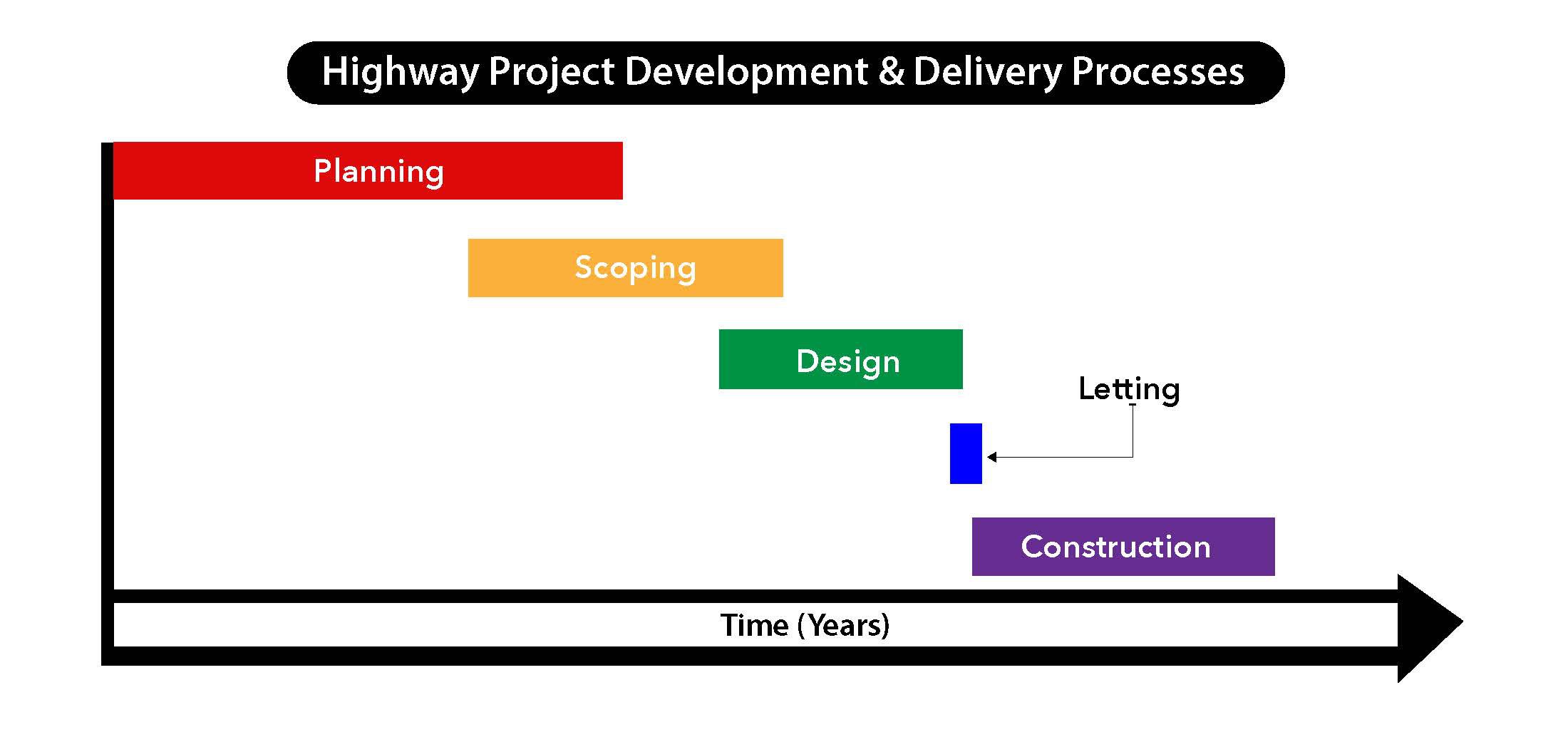

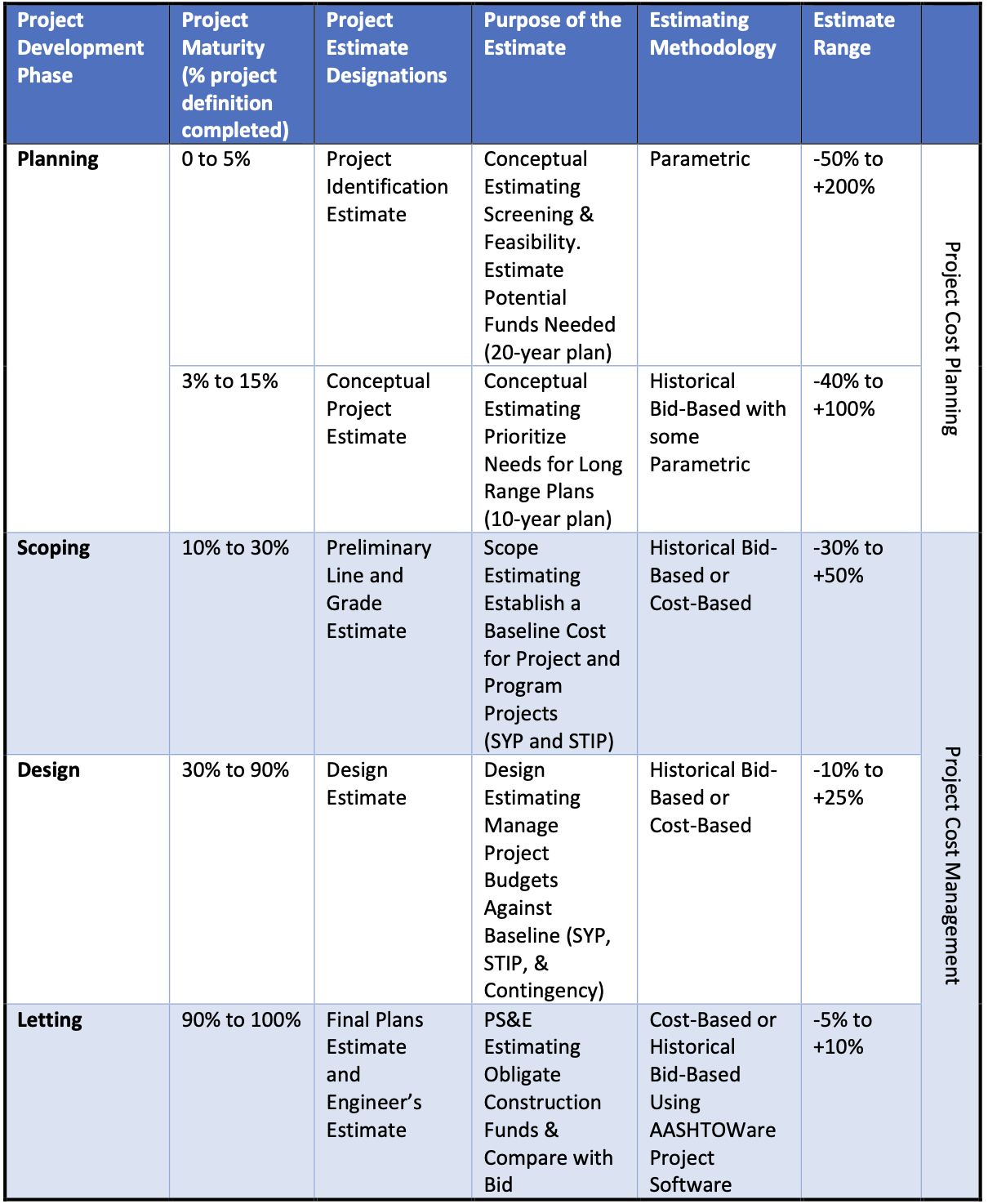

Developing estimates and progressively refining their accuracy throughout project development is integral to project cost planning and management. For each type of estimate, Figure 1 identifies the point in the project development process it occurs, its designation and purpose, method(s) used, and anticipated accuracy. Accuracy improves as a project moves through the development process and the scope becomes better defined.

AASHTOWare Project Estimation can be used to develop estimates, facilitate project cost management, and store highway construction bid history. Currently, KYTC only uses the software for the Engineer’s Estimate. Section 5 provides more information on this software. For highway project expenditures such as Right-of-Way Acquisition and Utility Relocation, the PM works with subject-matter experts (SMEs) to create estimates, track costs, and make payments. SMEs have access to historical pricing used to prepare estimates. PMs should consult SMEs when compiling project estimates for all phases.

The Cabinet uses three methods for estimating project costs: 1) parametric, 2) historical bid-based, and 3) cost-based.

Parametric Estimation:

- Cost parameters are developed and used to price a standard section of a given unit (e.g., linear mile, square feet, acre). This method produces estimates that can vary greatly from the actual costs incurred as a project moves through the project development process since a minimal amount of information is available. Estimates for Design, Right-of-Way Acquisition, Utility Relocation, and Construction are developed separately based on standard, high level pricing. SMEs in the various sections within KYTC District Offices should be included in the process.

Historical Bid-Based Estimation:

- Unit prices and quantities from previously let construction projects are available to generate estimates and improve accuracy. Prices are adjusted according to factors such as location, market conditions, scheduling, materials availability, and quantities. This method is first used in the latter stages of Planning and continues throughout the rest of project development.

Cost-Based Estimation:

- Cost-based estimation is a process of estimating unit bid prices by summing the costs of materials, equipment, and labor required for the unit of work. Cost-based estimates account for factors such as event sequencing, production rates, and contractor overhead and profit. Reliable cost-based estimates demand a solid working knowledge of construction industry practices and current market trends.

Methods can be used in combination to prepare a single estimate. For example, to incorporate current prices, the PM may develop a cost-based estimate for items that account for a larger portion of the project’s overall cost while adopting historical bid-based estimating for less expensive items. Estimates completed in this manner may be more accurate than estimates created using a single method.

Figure 1 – KYTC Project Development Phases Sequencing (After MnDOT (2008), Figure II.1-1). While not shown, the Right-of-Way Acquisition and Utility Relocation Phases normally begin near the end of or just after the Design Phase and can overlap into the Letting Phase.

2.1 Planning Phase

Highway system needs and deficiencies are identified during the Planning Phase to determine which projects can advance a region’s long-term goals. Area Development Districts (ADDs), Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs), District Offices, local officials, and other entities can propose projects to address safety, operational, or other transportation system needs. Needs are prioritized based on available funding and level of importance to the system.

Typical Planning Phase activities include:

- Develop a draft purpose and need statement

- Define a general project scope and develop Project Identification Estimate

- Identify potential risks or uncertainties

- Identify environmental red flags

- Initiate public involvement

- Study improvement concepts that meet the draft purpose and need statement

- Develop a Conceptual Project Estimate

2.2 Scoping Phase

During Scoping, alternatives that satisfy a defined need are investigated by the Project Development Team (PDT) to understand issues that could affect a project’s quality, cost, and schedule.

Typical Scoping Phase activities include:

- Refinement of project requirements and risks

- Forecast traffic growth

- Surveying

- Applicable environmental investigations

- Public involvement

- Analysis of improvement alternatives

- Preliminary identification of right-of-way and utility impacts

- Development of Preliminary Line and Grade Estimate

The Scoping Phase should result in selection of a preferred alternative in accordance with guidance in the Highway Design Manual (Section 203, Preliminary Design).

2.3 Design Phase

During Design, the PDT prepares detailed design plans for right-of-way acquisition and utility relocation as needed, and project construction. Environmental permitting may also be initiated and completed. By the end of the Design Phase, construction plans are complete and used to prepare the final documents for project letting. Design Estimates are prepared and updated as needed throughout this phase. The Joint Inspection Estimate is prepared as a major milestone during the Design Phase.

2.4 Letting Phase

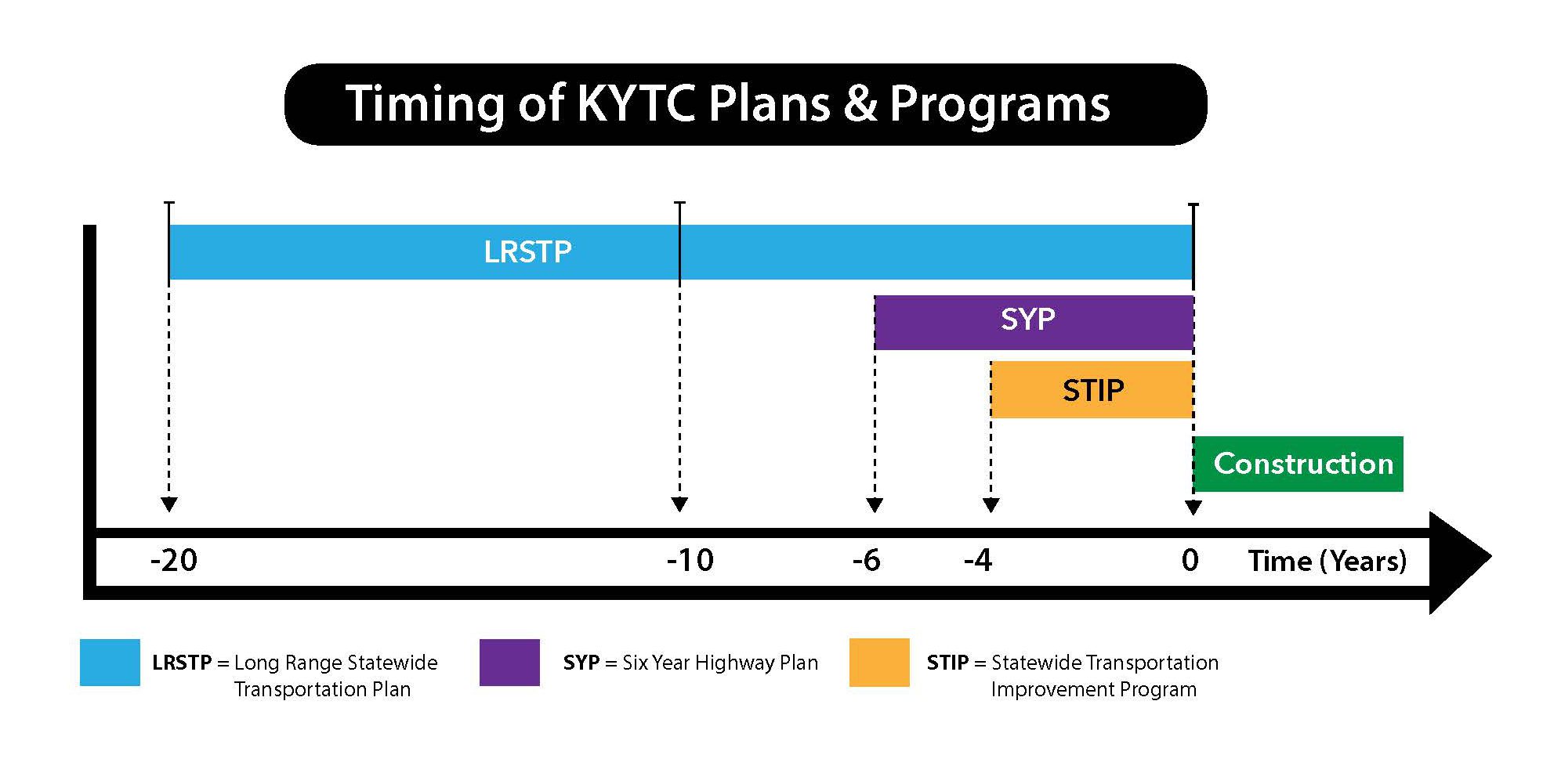

Letting immediately precedes construction. Key activities include preparing bid documents, completing the Final Plans Estimate and Engineer’s Estimate, advertising the project for construction procurement, evaluating submitted bids, and awarding the contract. Figure 2 depicts the general timeline from project conception to project construction.

Figure 2 – Timeline of KYTC Planning and Program Activities (After MnDOT (2008), Figure II.1-3)

The amount of time needed for Planning and Scoping depends on a project’s complexity and magnitude. Figure 3 approximates the duration of each phase for different project types. For minor, less complex projects, the Design Phase may be shorter and longer for large, complex projects.

Figure 3 – Typical Project Development Timelines (After MnDOT (2008), Figure II.1-4)

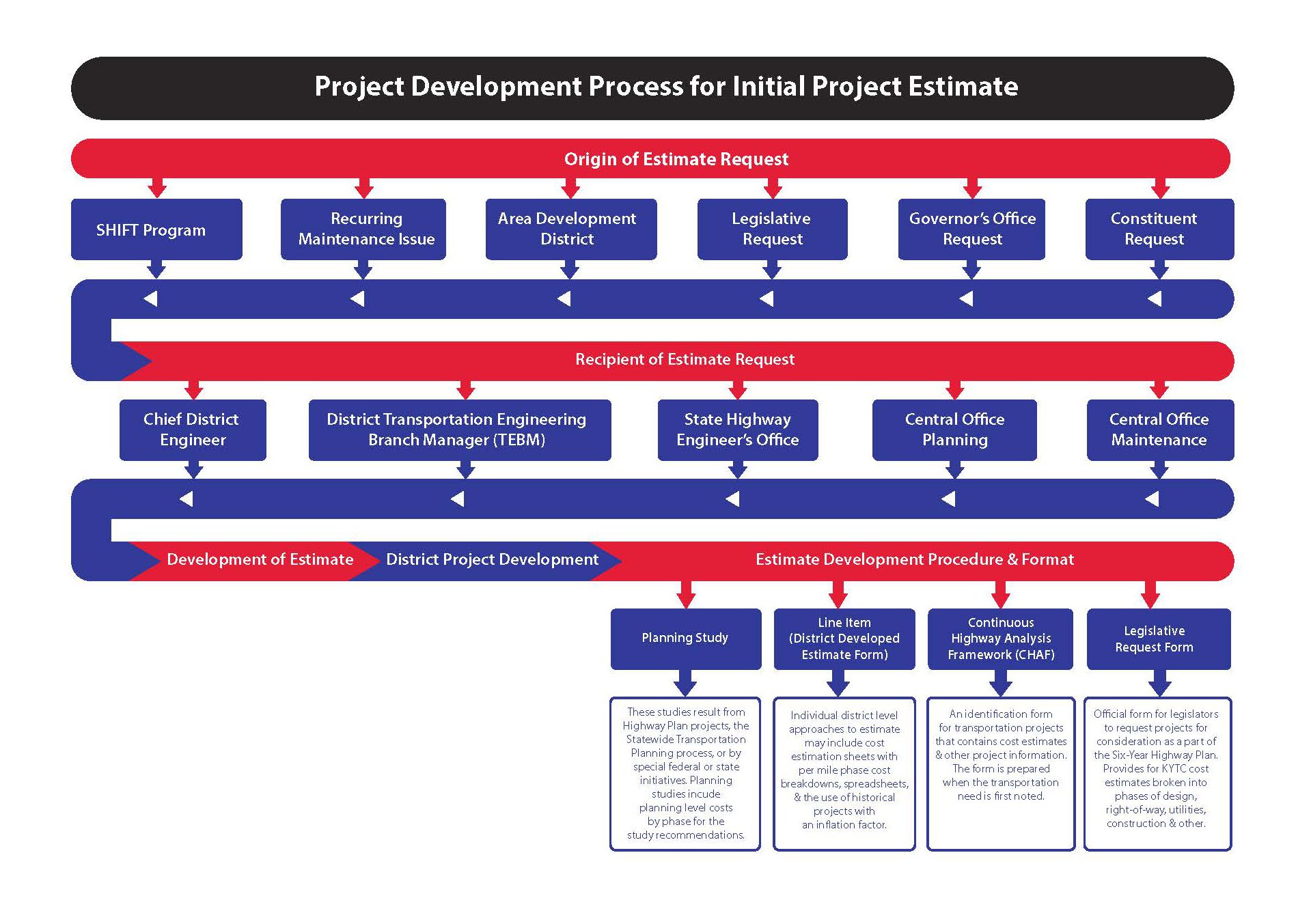

Project estimation and cost management is a continuous process that lasts throughout a project’s life cycle. The project development process typically requires several years to move from the Planning Phase to the Letting Phase. The first step is an initial request for a project estimate that sets the stage for budgeting and establishes a baseline for future estimates. Figure 4 depicts the initial project cost estimation process from request to development of the estimate.

3.1 Cost Estimating Throughout the Project Development Process

Projects are initiated when transportation system performance needs are identified and prioritized. Planning Phase estimates gauge the cost to deliver a solution that meets the project needs. When project development begins, a project is not well-defined and specific work items are unknown or unquantifiable. Consequently, generating detailed cost estimates at this stage can be challenging. Cost data from previous projects can serve as the basis for estimates. To prepare a reliable estimate for a new project, the PM should identify similar projects designed, constructed, or recently completed.

Characteristics important to consider when deciding if a project is similar enough to be relevant include:

- Proximity to the new project

- Rural or urban context

- Number of lanes

- Topography and landscape configuration

- Amount of right-of-way that needs to be acquired

- Typical roadway cross section

- Number and lengths of bridges

- Number and types of utility relocations

Table 1 identifies points in the project development process where estimates are required, their designation and purpose, the probable method(s) used, and the anticipated accuracy.

Table 1 – KYTC Project Cost Estimation through the Project Development Process

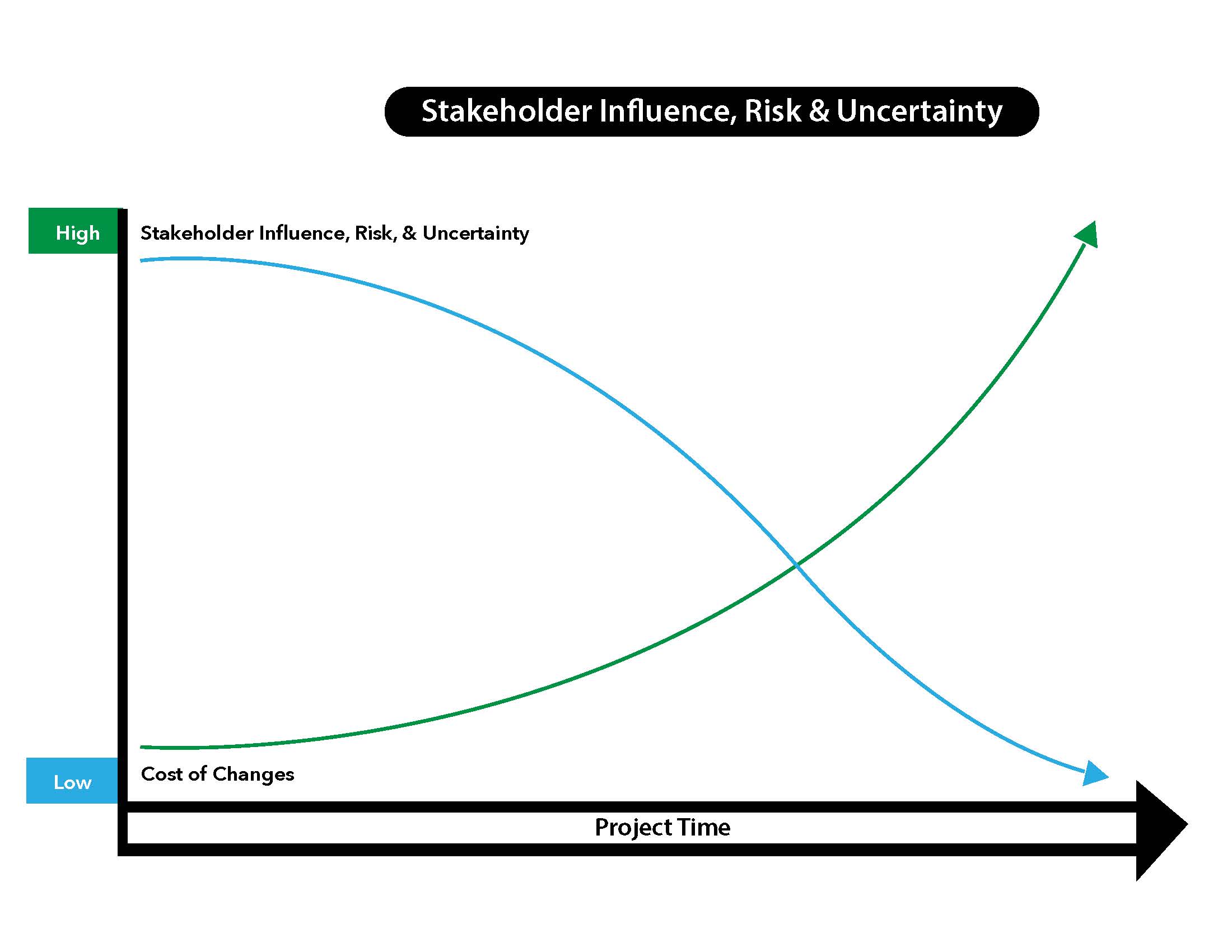

In terms of scope adjustments, PMs are most able to influence project costs during Planning and Scoping. Making changes early in the project development process is less expensive and introduces fewer risks than introducing modifications later. Figure 5 illustrates the general impact of design changes on cost and risk as a project moves through project development. Changes are more readily absorbed into existing budgets at the early stages due to the typical ranges of estimate accuracy shown in Table 1.

Figure 5 – Relationship Between Stakeholder Influence, Risk, and Uncertainty of Cost Changes (Source: PMI (2008), Figure 2-2)

PMs should be mindful of the different project phases that can be required and funded on a project. The SYP contains a budget and schedule for Design, Right-of-Way Acquisition, Utility Relocation, and Construction (DRUC). A DRUC budget represents the total project cost along with permitting and environmental mitigation fees as applicable. The PM and PDT should always be evaluating design changes that could reduce project costs while still fulfilling the purpose and need. Reducing overall project costs may increase cost in another functional area. For example, a suggested change may increase right-of-way costs but reduce construction costs by a greater amount, lowering the overall project cost.

The PM manages project costs by:

- Reviewing and approving significant work items and project milestones

- Communicating estimates to District and Central Office leadership, as appropriate

- Monitoring the scope and project conditions

- Evaluating the impact of changes

- Mitigating project risks

- Revising estimates when necessary

A PM should continuously monitor the dynamic relationships between the project scope, estimates, and budget. If the project scope is modified, the estimate and/or budget will likely require updating. A PM must evaluate and document through meeting minutes and other official project documentation the degree that scope changes will influence the estimate and/or budget. To ensure a PM is aware of the impact of scope changes on project cost, updated cost estimates are required at specific milestones within the project development process.

3.1.1 Planning Phase

Two estimates are created during Planning: (1) Project Identification Estimate and (2) Conceptual Project Estimate. Typically, the District Planning Engineer and the Project Development Branch Manager oversee Planning Phase estimates, with the Division of Planning serving as a source of information and support. The Division of Planning collaborates with the State Highway Engineer’s Office and Division of Program Management to generate project information that informs the SYP when needed. A preconstruction PM is typically not assigned until the end of Planning. However, during Planning, a PM should be involved and provide input. Planning Phase estimates, specifically the Conceptual Project Estimate, are typically the outcome of a planning study. The scope and level of effort are usually commensurate with project size.

Planning occurs before a budget is authorized. After a project budget appears in the SYP, scope changes affect the estimate and potentially the budget if funding is insufficient to deliver the project based on the new estimate. Establishing a well-defined scope as early as possible improves estimate accuracy and reduces the potential for costly scope changes in the future.

Project Identification Estimate – The Project Identification Estimate is the first cost estimate generated after a potential project is identified. The need for a potential project provides a basis for developing general project concepts and understanding the level of complexity. Since projects are not well-defined at this phase, parametric techniques are generally used to prepare estimates. The basis for this estimate could be an abbreviated planning study or a project definition with estimated costs based on similar past projects. The project definition and this estimate establish a baseline for consideration and prioritization in the appropriate KYTC program.

Conceptual Project Estimate – Before a Conceptual Project Estimate can be prepared, a project must undergo concept development. The purpose of concept development is to investigate project concepts and needs, determine whether it is feasible to advance the project, and establish programmatic assignments (e.g., major construction, reconstruction, resurfacing, safety, bridge, operations).

The Conceptual Project Estimate should use the highest level of detail available for quantity takeoff with the most recent bid information. The estimate accounts for the future project funding needs, including non-construction expenses such as Right-of-Way Acquisition and Utility Relocation. When estimating non-construction expenses, a PM should consult with the SMEs for each area. To identify high risks, assumptions that underpin this estimate should be documented.

Project conceptualization can help identify whether the environmental, social, or economic impacts are sufficient to require a Categorical Exclusion (CE), Environmental Assessment – Finding of No Significant Impact (EA-FONSI), or Environmental Assessment – Environmental Impact Statement (EA-EIS). By the end of Planning, the concept and basic project construction scope are in place.

3.1.2 Scoping Phase

The most critical project needs are carried forward into the Scoping Phase. During this phase, the Preliminary Line and Grade Estimate is prepared after the design of alternatives is complete. Near the end of this phase, the PM and the Project Development Branch Manager complete estimates for all alternatives considered, including Right-of-Way Acquisition, Utility Relocation, and Construction. The roadway design team prepares the roadway construction cost estimate. SMEs should be consulted to provide estimates for their respective areas, offer input on risks and contingency, and participate in reviews.

Preliminary Line and Grade Estimate – A Preliminary Line and Grade Estimate may be the most critical estimate developed during the entire project development process. It is used to determine the cost of each alternative. The PDT relies on these estimates to aid in selection of the preferred alternative, which moves forward into the Design Phase. The Preliminary Line and Grade Estimate is also typically used to program funding in the SYP for Right-of-Way Acquisition, Utility Relocation, and Construction.

3.1.3 Design Phase

The Design Phase focuses on developing detailed roadway and structure design for construction plans. Final right-of-way plans are developed so that right-of-way acquisition can commence if funding is available. Utility impacts are coordinated with utility owners who may use their own staff or design consultant to prepare relocation plans or may allow the relocation design to be included in the project Design Phase. The Right-of-Way Acquisition and Utility Relocation Phases regularly overlap with the Design Phase. Environmental permitting processes are usually completed during the Design Phase.

Throughout the Design Phase, a PM should monitor ongoing design work to ensure unnecessary additions to the scope of work are not included. Project cost management involves monitoring costs in response to (1) additions to or deletions from the project baseline definition or (2) changes resulting from development of the design or from changed site conditions. As a project moves through Design and becomes better defined, changes will likely need to occur. Design Estimates are updated to reflect the potential cost impacts of changes and reviewed to identify significant deviations from the budget.

Typically, the PM and Project Development Branch Manager are responsible for Design Estimates. The roadway design team prepares roadway construction cost estimates while SMEs from other divisions update estimates for their respective functional areas, including Right-of-Way Acquisition, Utility Relocation, environmental permitting, structures, and others as needed. The PM is responsible for identifying the needed disciplines and coordinating their contributions.

Design Estimates – While detailed design work is ongoing, the PM continuously oversees the design to identify any deviations from the baseline project definition and estimate. Current Design Estimates should be maintained and compared to the project budget to ensure that project costs stay within the programmed budget. If the PM and PDT decide the scope should be modified, appropriate justification and request for approval of the change should be provided to the State Highway Engineer’s Office. If a change request cannot be justified, the change and its associated costs should be removed.

Design Estimates, including those for other functional areas, are prepared (1) when the SYP is produced every two years, (2) at project milestones such as Joint Inspection, (3) when the project scope changes, and (4) upon request. Project budgets are typically updated when the project (1) is in the SYP, (2) has not been constructed, and (3) will remain in the next SYP. Potential reasons for a budget revision include:

- A scope adjustment not reflected in the previous SYP estimate

- Fluctuations in material and labor costs

- Cost variations for Right-of-Way Acquisition or Utility Relocation

- Inflation

3.1.4 Letting Phase

In the Letting phase, responsibility for project oversight shifts to Central Office Construction and District Project Delivery and Preservation personnel. The PM and PDT are responsible for delivering Final Contract Plans, including the Final Plans Estimate. The PM is also responsible for establishing the construction contract time in coordination with the Division of Construction and PDT. A PM should be aware that the contract time allowed for construction can significantly impact project costs.

After the Final Contract Plans and Final Plans Estimate have been submitted to the Division of Construction Procurement, its Estimating Branch prepares the Engineer’s Estimate. When construction bids are opened, they are compared to this estimate. If major differences exist between the Final Plans Estimate and Engineer’s Estimate, they are reconciled before the Engineer’s Estimate is finalized. Upon completion, the Engineer’s Estimate is sealed until bid opening day.

Letting phase estimates are developed to mimic contractor bids as closely as possible. Those responsible for preparing the Final Plans Estimate and Engineer’s Estimate should be aware of factors that influence pricing. Some examples are shown below. Many of these factors increase costs. For example, extensive environmental mitigation or material shortages increase prices. Conversely, some factors can reduce costs such as decreasing commodity prices. The factors listed tend to only be considered in the later stages of the project development process because it may be difficult to anticipate most conditions years in advance.

- Restrictions on work hours

- Material shortages

- Timing of advertisement

- Need for handwork

- Need for specialty work

- Extent of environmental mitigation

- Constructability issues

- Restrictions on maintenance of traffic methods

- Provision of work area for contractor staging

- Contractor availability and concurrent operations

- Pricing trends

-

Market competition

Final Plans Estimate – Also referred to as the Field Estimate, the Final Plans Estimate is based on definitive contract documents that reflect the project’s final design. This estimate is used to finalize project funding prior to soliciting bids and is compared to the Engineer’s Estimate. The Final Plans Estimate is created by the PDT, which has the most knowledge of the project. This estimate should be reasonably accurate, given the level of design it is based on. Prior to letting, the Division of Program Management may check for discrepancies between the Final Plans Estimate and the programmed construction amount documented in the SYP.

Engineer’s Estimate – This estimate is developed for the evaluation of contractor bids. It reflects the project definition presented in the final contract plans and specifications. This independent estimate is developed by staff specialized and knowledgeable of the current bidding environment and is sealed until the bids are publicly announced on letting day. Intended to mimic contractor bids, current market conditions play an important role in its preparation. The Engineer’s Estimate represents the fair and reasonable cost to construct a project using the best available information on current material, labor, and equipment costs including overhead and profit. KYTC’s Awards Committee uses the Engineer’s Estimate as a benchmark for analyzing bids and determining whether to award a construction contract. The estimate is an essential element in the Construction Procurement process.

3.1.5 Escalation

Many years can pass between project conceptualization and construction. Inflation can significantly increase the construction cost of a project in just a few years. Historically, the amount of funding available has not typically kept pace with inflation. KYTC escalates cost estimates for inflation based on the expected year of construction. During the Planning Phase, it is likely a construction year will not be set. As a result, the basis for escalation of a project at that time is difficult to determine. As projects transition into Scoping and Design, the desired year of construction generally becomes known, or is narrowed down to a short time range. Estimates developed during the Scoping and Design Phases should be escalated based on the best estimates of future inflation rates. It is important for program management purposes that PMs use all information available to provide the best possible cost estimates for the year of expenditure and the Division of Program Management identifies appropriate escalation rates for use. This enables KYTC to better forecast expenditures in relation to anticipated future funding amounts.

3.2 Project Cost Management and the Role of Budgets

Project cost management techniques are applied throughout Scoping, Design, and Letting. A cornerstone of project cost management is continuous oversight of the project’s definition. A PM cannot let scope creep alter a project and increase cost. If the original purpose and need remains unchanged, the project definition should not change, and estimated project costs should be measured against the project budget programmed in the approved SYP. Because that project budget is legislatively enacted, it is imperative that project costs remain within the budget. Exceeding a budget imperils other projects by reducing the limited amount of funds available for them. If the costs on one project increase, schedules and budgets found in the SYP are directly impacted. As these impacts accumulate, KYTC is forced to make tough decisions about which projects receive funding, resulting in delays and cancellations. Failure to deliver projects erodes the public’s trust in KYTC.

Sometimes, revising budgets is unavoidable. Situations in which a PM may need to prepare an updated estimate to revise the budget include (1) when a scope change has been approved, (2) before a new SYP is issued, and (3) upon request. A PM must inform the State Highway Engineer’s Office of proposed changes that will impact costs and formally request authorization to make those changes.

Before requesting a budget increase, a PM should determine whether the original budget includes sufficient contingency to pay for the proposed changes, if costs can be reduced in another phase area (R, U, or C phases) to accommodate the proposed changes, or if the project design can be modified elsewhere to reduce project costs and absorb the increased expenses without compromising the project’s ability to meet the purpose and need.

Understanding project contingencies is critical for developing accurate estimates. Contingencies are incorporated into estimates to account for 1) exposure to risks and uncertainties that influence project costs, 2) minor work items that are not quantified when the estimate is created, and 3) inaccuracies introduced when broad-based assumptions are necessary, especially during initial stages of the project development process. The magnitude of contingency as a percentage of a project should decrease as a project moves through the development process.

For highway projects, the following contingencies are typically included:

- A planning or design contingency based on project maturity (i.e., the percentage of the project completed)

- Risk contingencies to account for perceived potential risks and potential changes due to changed conditions (i.e., environmental concerns, utilities, challenging right of way)

- Construction contingency for work completed by KYTC during construction

- An overall Program Management contingency to help leadership with cash-flow management

The Highway Design Manual (HD-204.16.1) specifies fixed percentages to add to the overall project cost for Construction Engineering and Inspection (CE&I). CE&I is added to the construction estimate to cover services required for:

- Construction contract administration

- Construction engineering and inspection

- Materials sampling and testing

For projects with construction costs less than $1 million, a 15% contingency is added for CE&I. For projects with construction costs greater than $1 million, a 10% contingency is added. CE&I funds are used to pay for KYTC construction management and minor construction change orders that may arise. Reserving these funds within the construction-phase budget provides some fiscal margin without having to request additional money or reallocating funds from other projects.

All PMs should be in the habit of identifying and managing risks. Risks are uncertain events that can influence, positively or negatively, the attainment of a project’s goals and objectives. When a project begins, a PM must identify and document risks that may affect project delivery and account for them by adding contingencies to the estimate and time to the project schedule, as applicable. Below are some potential risk factors for PMs to consider.

- Project setting – project location and characteristics (e.g., isolated rural areas, urban landscapes, narrow corridors, mountainous terrain)

- Availability of contractors and materials

- Project complexity and size

- Issues related to traffic control, railroads, right-of-way, utilities, and geotechnical factors

- Environmental issues and mitigation

- Changed conditions and the potential for associated change orders

- Inaccuracies due to level of design completed

- Incorrect quantities or unit costs

PMs can use a risk register to document, monitor, and manage risks. A risk register is a tool in risk management and project management used to identify potential risks and document the nature of the risk, the level of impact the risk could have, the party that can best manage the risk, and the appropriate risk response mitigation measures. A risk register should include the following information for each risk:

- A description of each risk

- Probability of occurrence

- Potential impacts to cost and schedule

- Party responsible for mitigation of the risk

- Measures to mitigate the risk

On minor projects, it may be sufficient to address risks by applying a standard contingency without developing a comprehensive risk register. As project complexity increases, keeping an updated risk register assumes greater importance and is critical for organizing work activities. On complex projects, a PM can benefit by categorizing contingencies (e.g., structures, utilities, right-of-way) to generate a clearer picture of risk distribution across the project.

Identifying risks on each project can be challenging. PMs benefit from studying known completed and ongoing projects with similar characteristics to get a sense of risks they are likely to encounter. Other strategies for identifying potential risks include speaking with other PMs and SMEs in the District and Central Office and conducting detailed site visits to acquire firsthand knowledge of factors that could increase costs. The latter includes topography, traffic volumes, utilities, accessibility, and challenges contractors may confront with staging and operating equipment. Because no universally applicable formula exists for determining appropriate contingencies, a PM should dedicate time and effort to build their knowledge of risk factors and how interactions between risk factors can affect the delivery of different project types.

The amount allocated for contingencies should decrease as a percentage of overall project cost as a project moves from Planning to Letting, and as risks are unrealized, mitigated, or eliminated. Table 2 lists approximate percentages for contingencies for medium to high-risk projects at each project phase. Percentages are usually smaller on lower-risk projects such as safety, pavement rehabilitation, or maintenance projects. When a specific risk is no longer a concern, it should not be factored into contingencies developed for future estimates or be used to expand the project scope.

The percentages in Table 2 are a general guide. PMs should consider their knowledge of a project and use engineering judgment to identify risks, potential impacts, and appropriate contingencies for each project.

Table 2 – Typical Contingency Percentages by Project Phase

| Project Phase | Contingency (% of Overall Project Costs) | |

|---|---|---|

| Planning | 25% - 30% | |

| Scoping | 15% - 20% | |

| Design | 10% - 15% | |

| Letting – Contingency shown is primarily for construction engineering and inspection costs. It is included here since it is intended to cover minor change orders that may arise. It may be prudent for a PM to include additional contingency for the Construction Phase. | Project Construction Cost < $1 million – 15% Project Construction Cost ≥ $1 million – 10% |

4.1 Examples

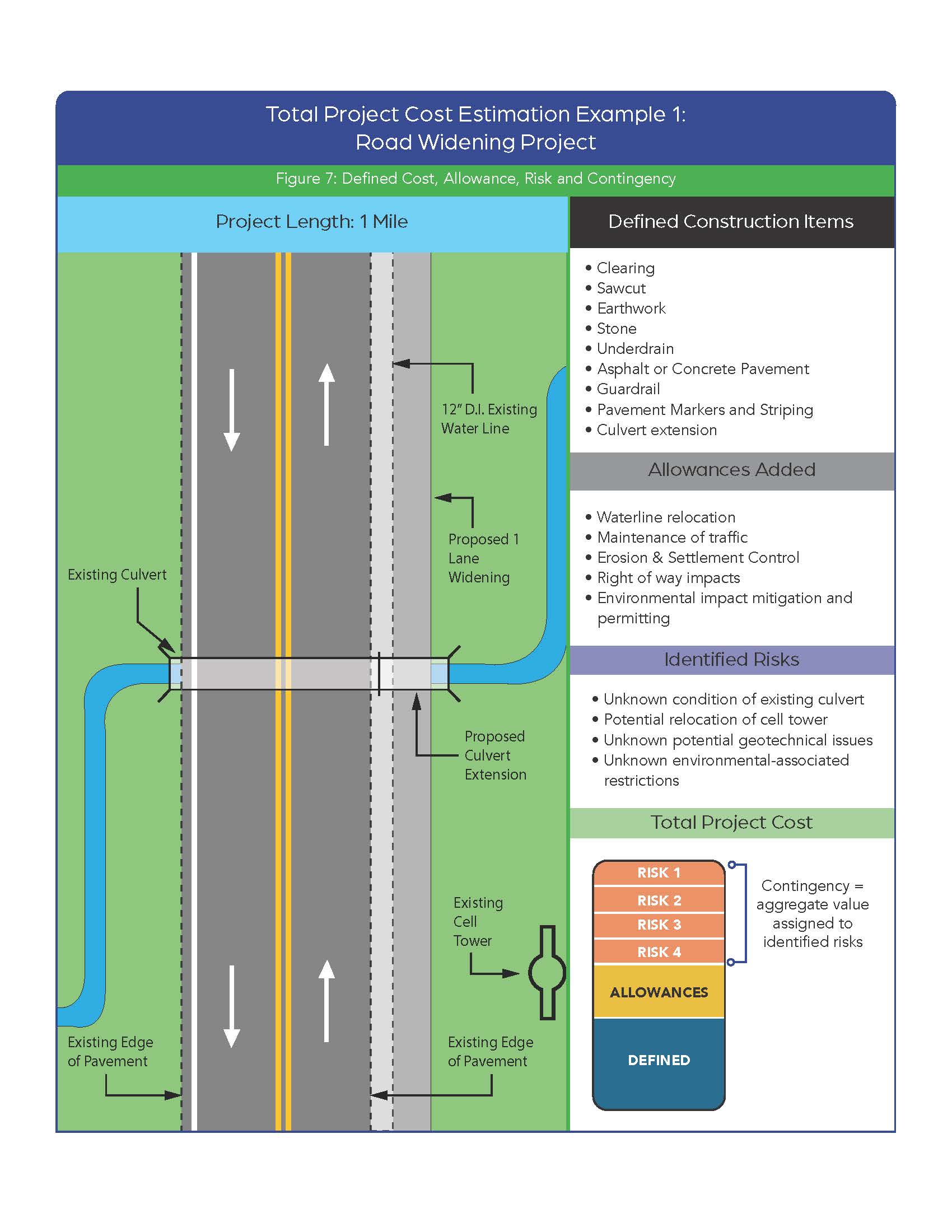

Figures 6 and 7 on the following pages depict two examples of total project cost estimation during the early stages of the project development process. For most projects, certain construction items can be defined at any stage. For example, pavement quantities for a road widening project can be estimated with an appropriate pavement design based on similar completed projects. These items are “Defined Construction Items”.

The project in Example 1 is expected to require relocation of a 12-inch ductile iron water line. While cost for the length of water line can be easily estimated based on historical prices, factors such as related facilities within the corridor or special requirements of the utility company may be unknown. Likewise, mitigation costs for the existing stream or tree removal can be estimated but could vary significantly pending further design decisions and additional information acquired from outside agencies as the project development process continues. These costs are defined as “Allowances Added”.

Finally, potential risks should be identified. In Example 1, an early project cost estimate may be completed without a field visit. As a result, the unknown condition of the existing culvert that is to be extended is an “Identified Risk”. Without a site visit, a PM should assume that replacement of the entire culvert may be necessary. The summation of estimated costs assigned to each potential identified risk is the contingency. The sum of estimated costs for “Defined Construction Items”, “Allowances Added”, and “Identified Risks” results in the total project cost estimate.

Figure 6 – Example 1 – Total Project Cost Estimation (Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Cost Estimating Manual, (2021), Figure I-1a)

Figure 7 – Example 2 – Total Project Cost Estimation (Source: Virginia Department of Transportation, Cost Estimating Manual, (2021), Figure I-1b)

AASHTOWare Project Estimation is a web-based application that streamlines, simplifies, and improves the organization of project-related data and project cost management activities. Because the software consolidates bid histories, users can view information on historical pricing trends. AASHTOWare Project Estimation can be used throughout the project development process. Currently, the Engineer’s Estimate is being developed with the software while the remainder of estimates are typically developed with AASHTOWare Project Estimator. Appendix D of a Draft Guidance Manual published by the Cabinet reviews the features and layout of the more robust software platform, provides step-by-step directions for navigating its interface, explains how to populate project files with data, and defines the categories and fields that users encounter. A video tutorial is also available on YouTube at this Link.

AASHTOWare Project Estimation holds several advantages over the traditional methods of preparing estimates such as spreadsheets and the AASHTOWare Estimator software. In some cases, a PM may need to rely on those conventional procedures, especially when an estimate is needed on short notice. However, automating the estimation process through AASHTOWare Project Estimation will minimize errors and improve uniformity. As always, to be successful, PMs must strive to collect quality data for input in the estimation process.

References

American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO). (2013). Practical Guide to Cost Estimating. AASHTO.

Connecticut Department of Transportation. (2019). Connecticut Department of Transportation 2019 Estimating Guidelines. https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/DOT/documents/AEC/Cost_Estimating/CTDOT_Est_Guide_2019_June.pdf

Georgia Department of Transportation. (2014). Inter-Department Correspondence on Cost Estimates. http://www.dot.ga.gov/PartnerSmart/DesignManuals/EngineeringServices/Guidance%20on%20Updating%20Cost%20Estimates.pdf

Gransberg, D.D., Jeong, H.D., Craigie, E.K., Rueda-Benavides, J.A., Shrestha, K.J. (2018). Estimating Highway Preconstruction Services Costs — Volume 1: Guidebook. NCHRP Report 826. Transportation Research Board.

Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT). (2008). Cost Estimation and Cost Management Technical Reference Manual. https://edocs-public.dot.state.mn.us/edocs_public/DMResultSet/download?docId=1846457

New Jersey Department of Transportation. (2019). Cost Estimating Guideline. https://www.state.nj.us/transportation/capital/pd/documents/Cost_Estimating_Guideline.pdf

Project Management Institute (PMI). (2008). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (Fourth Edition).

Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT). (2021). Cost Estimating Manual. https://www.virginiadot.org/business/resources/Cost_Estimation_Office/VDOT_Cost_Estimating_Manual.pdf

Project Management Guidebook Knowledge Book:

Access the complete Knowledge Book here: Project Management Guidebook

Next Article: Assembling a Project Development Team

Previous Article: Project Schedule & Development of Milestones

Time Management for Highway Project Development Knowledge Book:

Access the complete Knowledge Book here: Time Management Knowledge Book

Next Article: Develop Preliminary Alternatives

Previous Article: Data Gathering