Search for articles or browse our knowledge portal by topic.

Project Scoping

| Project Scoping | Project Classification | |||

| Capital Improvement Projects | Safety Projects | Asset Management Projects | Maintenance Projects | |

| 1.0 Overview | x | x | x | x |

| 2.0 KYTC Transportation Project Scoping | x | x | x | x |

|

2.1 Capital Improvement Projects |

x | |||

|

2.2 Safety Projects |

x | |||

| 2.3 Asset Management Projects | x | |||

| 2.4 Maintenance Projects | x | |||

| 3.0 Defining the Project | x | x | x | x |

| 4.0 Project Coordination | x | x | x | x |

| 4.1 Scope Verification Meeting | x | x | x | |

| 4.2 Value Engineering | x | x | ||

| 5.0 P&N Development | x | x | x | |

| 5.1 How is P&N Developed? | x | x | x | |

| 5.2 Who Develops the P&N Statement and When? | x | x | x | |

| 5.3 Why is the P&N Statement Developed? | x | x | x | |

| 6.0 Performance Measures | x | x | x | x |

| 7.0 Additional Resources | x | x | x | x |

| 7.1 Additional Mapping | x | x | ||

| 7.2 Environmental Overview | x | x | x | |

| 8.0 Public Involvement | x | x | x | |

| x = Information from the topic may be applicable for the project classification. | ||||

When a project begins, the Project Manager (PM) collects and reviews existing project information (see HKP article on Project Initiation) to gain a basic understanding of the project’s objectives and identify knowledge gaps. Once these data are in hand, the PM can begin the scoping process. The goal of project scoping is to investigate the situation and develop a project description that addresses the project’s need(s). If the project scope is not clearly defined, revisions may be needed after the project has begun, leading to delays or overpromises of what can be delivered. Ideally, a reliable, decisive project scope is defined in the early phases of project development. The scope should include a project definition that clearly communicates the project scope’s framework and specifies what the project will and will not deliver.

“The scope should include a project definition that clearly communicates the project scope’s framework and specifies what the project will and will not deliver.”

Successful project scoping:

- Defines project boundaries

- Identifies project components

- Develops key design parameters

- Estimates a budget and schedule to an adequate level of detail for planning purposes

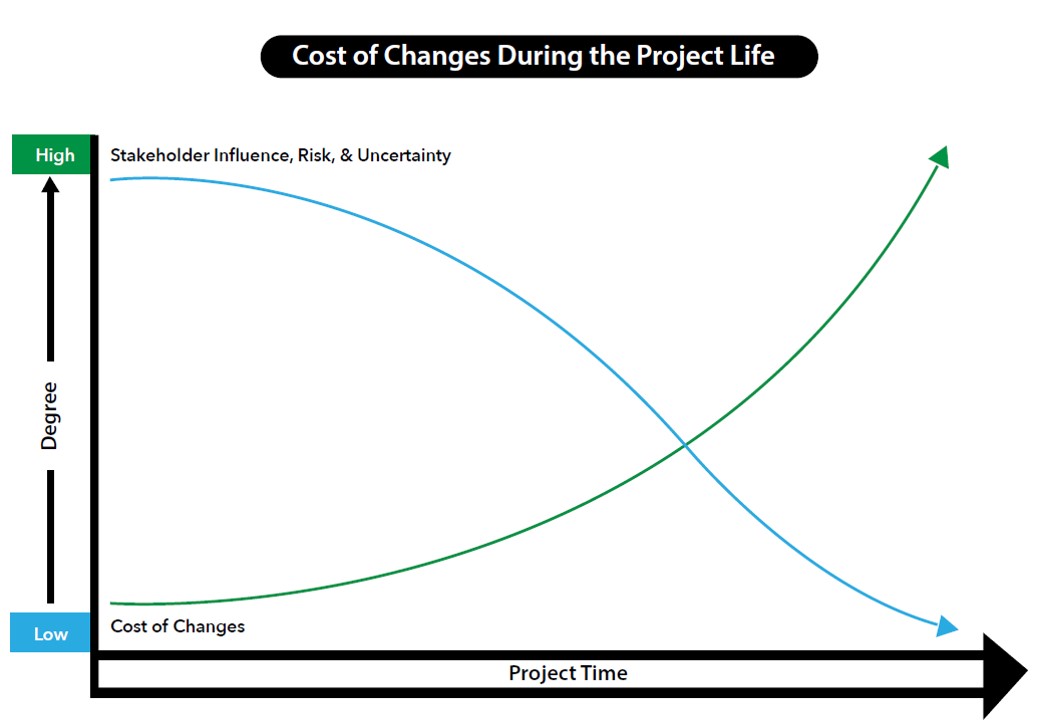

The PM is responsible for tracking the project scope throughout project development — from early scoping through letting. The project scope may be refined during preliminary designDefines the general project location and design concepts. It includes, but is not limited to, preliminary engineering and other activities and analyses needed to establish parameters for the final design.. During the last stage of scoping, the project scope, budget, and schedule are finalized. The budget developed at the end of the scoping phase is the Preliminary Line and Grade Estimate prepared after the design of the alternatives is complete. At this point, enough information is available to firmly establish the project parameters, including final designAny design activities following preliminary design and expressly includes the preparation of final construction plans and detailed specifications for the performance of construction work., right-of-way needs, existing utilities, environmental impacts, broadly accurate cost estimates, schedules, and staffing demands. Final scoping work is passed along to roadway and structure designers, and other subject matter experts depending on project complexity, to guide their efforts. At each milestone the PM should compare the initial project scope to the scope captured in previous project documentation. Scope refinement occurs throughout project development, but PMs should take special care to ensure the scope does not expand (i.e., scope creepAdding features (project scope) beyond what was initially agreed upon without addressing the effects on schedule, budget, and resources.). The ability to influence the final characteristics of the project’s product, without significantly impacting cost, is highest at the start of the project and decreases as the project progresses towards completion. The following figure illustrates the idea that the cost of changes and correcting errors typically increases substantially as the project approaches completion.

Inadequate scoping often results in significant cost increases, completion delays, and the constructed project performing poorly or being of substandard quality due to development constraints imposed by inaccurate estimates. Dedicating resources to robust scoping work is a proactive approach to project development and helps avoid unexpected problems that can jeopardize project completion. For more information on project scoping see KTC’s report Best Practices for Highway Project Scoping.

Red Flag

If a project requires further definition or a clearer scope, work with the Chief District Engineer (CDE) and Central Office subject matter experts (SMEs) to understand the project purpose and identify knowledge gaps. Consulting with the project sponsor may also help to clarify the project scope.

2.1 Capital Improvement Projects

A project usually starts with a problem or roadway need identified through the Continuous Highway Analysis Framework (CHAF) with a high-level scope and a compiled rating through SHIFT (see the HKP article Project Initiation). Most legislatively added projects receive Enacted Highway Plan funding without going through the CHAF/SHIFT selection process.

The District Office (DO), often in collaboration with Area Development District (ADDs) and Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs), typically provide a scope and cost estimate for these projects. If the projects are programmed into the Highway Plan, they are further scoped through the planning and preliminary design phase. See PL-702 and HD-202.6.3 for more information. The Project Time Management article includes flowchart examples of project scoping activities.

During the scoping process, it is important to right-size the potential project solutions, keeping in mind the context and the needs of the statewide transportation system. For more information see the PMGB article Flexibility in Design (coming soon).

2.2 Safety Projects

A range of project types are funded through the Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP). Projects are categorized according to how much scoping work is needed (i.e., number of hours) and the level of coordination among team members (Table 1).

| Table 1. Relationship Between Scoping Effort and Time Commitment | |

| Level of Scoping Effort | Time Commitment |

| Low | 1-2 months |

| Medium | 3-6 months |

| Medium-High | 6-12 months |

In general, administrative scoping (project evaluation, coordination, and refinement) increases with project difficulty. Some projects that need a medium – high level of scoping also involve engineering scoping, which may include investigating potential treatments to determine their impacts, benefits, costs, and other factors. When scoping requires more effort, PMs may need to conduct field visits or review conditions via PhotoLog. PMs should also review the crash data and other information described in the article Project Initiation.

Projects that Require a Low Level of Scoping (1-2 months)

The Central Office Traffic Safety Branch typically handles projects that entail the least amount of scoping. The Division of Maintenance provides matching funds. Project types in this category include:

- Systemic Intersection Improvements – This program uses Highway Safety Manual (HSM) methods to identify correlations between intersection characteristics and severe crashes. Low-cost improvements are identified and primarily include sign and signal changes.

- High Friction Surface Treatments – HSM methods are used to identify locations that can benefit from high friction surface treatments due to frequent crashes in wet conditions. These treatments apply high-quality aggregate to the pavement using a polymer binder.

- New Guardrail (FE06) Matching Funds – This program provides matching funds for the New Guardrail Program (FE06). The Maintenance Rating Program (MRP) identifies guardrail improvement locations based on severity of conditions.

- Cable Barrier – Delivered by the Central Office Division of Highway Design, this program evaluates interstates segments that do not have longitudinal barriers. Project locations are prioritized using a data-driven approach.

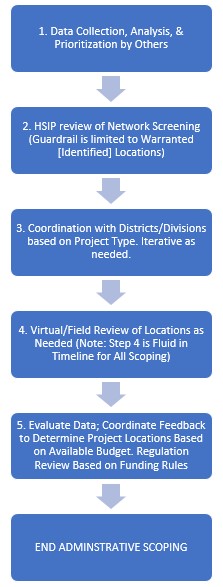

Figure 1 summarizes the process for scoping projects that require a low level of effort.

Projects That Require a Medium Level of Scoping (3-6 months):

Intersection Emphasis projects require a medium level of scoping and rely on DO knowledge of the local system. Often, the Divisions of Traffic Operations, Highway Design, and Planning participate at this level of scoping. HSIP’s biggest focus is Intersections and Roadway Departure Corridors, which account for more than 80% of the annual budget.

Highway Safety Manual (HSM) methods are used to evaluate the safety performance of intersections in each District. Generally, 5 – 10 intersections are selected in each District for further evaluation. This process includes field reviews, reviewing existing conditions, crash analysis, and identifying potential improvements.

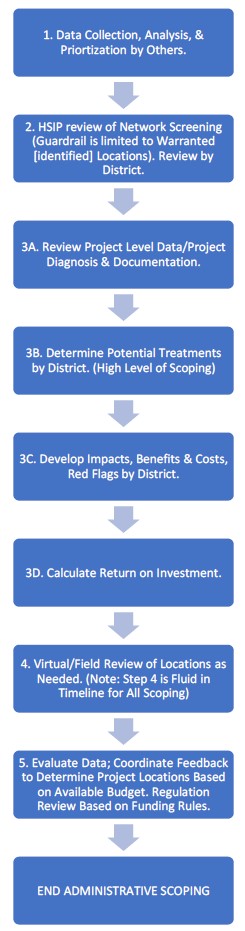

Figure 2 summarizes the process for scoping projects that require a medium level of effort.

Projects That Require a Medium – High Level of Scoping (6-12 months):

Projects that need a medium – high level of scoping are considered under the Roadway Departure Emphasis Program. Roadway Departure Emphasis improvements are studied within each KYTC District, including priorities and preliminary costs. Emphasis area studies include crash data review, GIS analysis, and virtual review (i.e., PhotoLog, StreetView) to identify locations where improvement projects have the greatest potential to reduce crashes.

The Roadway Departure Emphasis studies generally take 6-12 months, although planned modifications to the process should reduce the timeframe to 6-8 months. The studies will be repeated biannually. HSIP project types included in the studies include:

- Roadway Departure — This program focuses on rural, two-lane, roads with speeds over 50 mph. HSM methods are used to identify and prioritize locations for safety improvements (e.g., shoulders, rumble strips, slope, superelevation, culverts, ditching, signage, delineation).

- Shoulder Widening — Potential projects are identified using the Highway Information System (HIS), along with resurfacing priorities or the Roadway Departure Emphasis project list. Improvements include establishing or widening shoulders and evaluating projects for centerline and edgeline rumble strips.

- Horizontal Alignment Signing — This program identifies curves that would benefit from enhanced horizontal alignment signage, including fluorescent yellow sheeting. Project locations may be submitted by District staff for recently resurfaced corridors or for local routes with complete engineering studies.

- National Highway System End Treatments — Replacement of outdated guardrail (turn-down style) on National Highway System (NHS) routes is included in this initiative, but new barrier installations are not permitted. Districts research and document project locations.

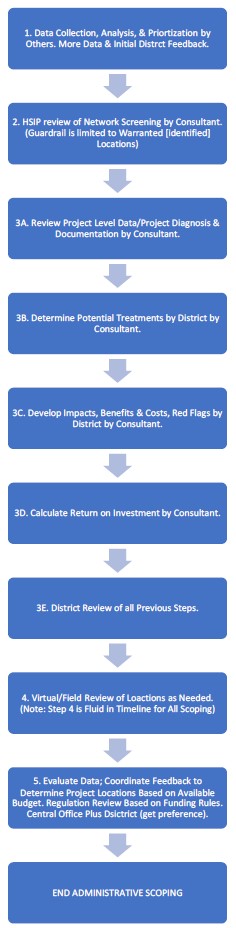

Figure 3 summarizes the process for scoping projects that require a medium – high level of effort.

2.3 Asset Management Projects

Scoping for asset management projects is generally constrained by the funding mechanism utilized. Projects that can be completed within a given program’s constraints receive priority. Those that cannot be completed with program constraints are analyzed as part of a separate prioritization process. This lets KYTC provide a streamlined process for projects that can be addressed with a reduced scope.

Pavement preservation projects funded through the FD05 or CB06 programs are typically limited to a single surface layer no more than 1.5” thick, with some allowances for minor base failure repairs and leveling material to address rutting or other cross-section deficiencies. Additional items included in pavement preservation projects are limited to those required to reestablish roadway functionality or to comply with federal-state agreements (e.g., striping, signal detection loops, pavement markings, ADA-compliant sidewalk ramps).

Scope constraints for bridge projects funded through the FE02 bridge maintenance budget are less strict than those applied to the FD05 and CB06 pavement programs. No definitive rule is in place that limits the type of work that can be performed with FE02 funding. But projects funded with FE02 are generally limited to maintenance and minor rehabilitation (e.g., deck rehabilitation, scour mitigation, painting, and low-cost preventive maintenance work). Bridges that require more significant rehabilitation or replacement are programmed through the Highway Plan process and prioritized and scoped through the bridge program.

KYTC’s asset management programs focus on maintaining and improving the condition of existing highway assets. To address the greatest number of assets with available funding, KYTC limits the breadth of individual project scopes. This strategy lets KYTC award a much larger number of asset management projects each year than would otherwise be possible, thereby providing greater value to the overall highway network.

Asset management projects utilizing federal funds require an approved National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) document. In most cases, impacts are minimal and apply to Categorical Exclusion (CEs). For more information on the level and scope of CE documentation, consult with the District Environmental Coordinator and see KYTC’s Categorical Exclusion Guidance Manual.

2.4 Maintenance Projects

While the capital improvement program adopts a more forward-looking view that emphasizes projects which improve mobility and economic development, the maintenance function focuses on the entire highway network’s immediate operational needs. The do-nothing option is rarely available if mobility has been compromised due to roadway damage or deterioration. When combined with the budgetary limitations of maintenance programs, this emphasis on network-level response encourages maintenance practitioners to constrain individual project scopes to maximize the impact of work performed.

KYTC maintenance projects primarily address immediate operational issues and make minor repairs to highway assets. To maintain mobility across the roadway network, maintenance staff must address emergency issues as soon as possible. To accomplish this, KYTC uses a tiered approach that encourages Districts to use the least complex scope which meets a project’s needs.

KYTC uses three mechanisms to address maintenance needs — in-house staff, master agreements, and defined-bid contracting. This framework constrains projects by simplifying the implementation of activities that have narrower scopes. While District maintenance staff can be deployed quickly to address urgent needs when they arise, the range of projects that in-house staff can perform is limited by the availability of requisite skilled personnel and equipment. At the other end of the spectrum, defined-bid contracts can be used for an almost unlimited range of projects. But they require more time, effort, and funding to carry out. Master agreements provide a middle ground, with a predefined set of activities at a known cost that are deployed relatively quickly but with some limits on speed and scope.

When faced with an operational challenge, District maintenance engineers are authorized to initiate a response using in-house staff or a master agreement if an applicable agreement exists within the geographic area of concern. The primary limitation in these cases is the availability of enough maintenance funding at the District level. If a District cannot perform the required work with its staff or a master agreement contractor, a defined-bid contract may be pursued. These cases require the involvement of Central Office staff to help develop a project proposal and identify necessary funding. In this way, project scopes are expanded only when a less complex method is insufficient for the task at hand.

Because potential projects have a variety of origins, not all projects have a thoroughly developed initial project definition when they are authorized. Early in the project, the PM must attain a clear definition of the project’s needs, purpose, goals, and scope.

A project definition should be established to clearly communicate the framework of the project’s scope. The definition should specify what the project will deliver and what it will not deliver. An unclear or inaccurate scope may require significant revisions once the project has been programmed, which can delay the project or cause KYTC to overpromise what it can deliver.

HD-202.6.3 lists items to help define the project. For many projects, the Enacted Highway Plan also provides the initial scope. The Enacted Highway Plan entries outline a project’s expectations, funding, schedule, and budget.

Note: Scope of work (SOW) describes the required processes and resources to complete a work. It is how a work group (usually a consultant team) plans to achieve project objectives. SOW outlines the tasks, expected deliverables, milestone schedule, work and work units, production hours, and is described in more detail in Section 2 of Managing Consultant Contracts. The SOW impacts project scoping, but they are different concepts.

Red Flag

When defining the project, clearly document the purpose and the limitations of the project and share this information with the internal and external project stakeholders. Scope creep is usually a result of not properly defining, documenting, or controlling the scope.

Once a project is authorized (see the article, Project Initiation), the PM and other project team members (see Assembling a Project Development Team – coming soon) should review issues confronting the project. This early coordination focuses on the project scope. Depending on how complex the issues are and the availability of team members, coordination can be done with a scheduled meeting, phone call, or email.

The PM should also check with other areas in the Department (e.g., Maintenance, HSIP) to determine if other types of identified projects at or near the location could be combined with their project. For example, a pavement preservation project and a safety improvement project could be combined into one project for the letting.

If FHWA selected the project to have federal oversight, the PM should coordinate with FHWA to accommodate their involvement activities. KYTC’s Division of Highway Design keeps a current list of projects with FHWA oversight.

4.1 Scope Verification Meeting

On federal projects with an anticipated CE Level 3 or above, PMs should organize a scope verification meeting in concert with Division of Environmental Analysis Environmental Project Mangers (EPMs) and Division of Highway Design’s Location Engineers. This meeting should be held before the pre-design conference to discuss the scope and potential environmental impacts. Identifying the anticipated type of environmental document informs the PM of the level of effort expected for the environmental process and facilitates contract negotiation. Participants should include the PM, FHWA representative, and other team members. HD-202.6.7 lists items that may be discussed.

If the project will modify interstate access, this meeting also presents an opportunity to discuss with FHWA the need for an Interchange Justification Study (IJS) or an Interchange Modification Report (IMR) and the level of traffic engineering analysis required (see HD 203.3.10 for more information).

4.2 Value Engineering

A VE study is an independent, systematic, creative analysis to analyze a project’s design or reduce its cost while still meeting the purpose and need of the project. If the total cost of a federally funded roadway project exceeds $50 million or the total cost of a bridge project exceeds $40 million, a Value Engineering (VE) study is required. A project manager may request a VE study on projects not meeting the cost thresholds to optimize designs and project costs. VE study recommendations are most beneficial shortly after the preferred alternative has been identified. Projects with narrower scopes may benefit from VE studies during final design. VE studies are administered through the Quality Assurance Branch (QAB) in the Division of Highway Design. The PM should coordinate with the QAB to schedule and implement the study.

Red Flag

If smaller projects are breakouts of a larger project with one environmental document, and the larger project meets the cost threshold for the VE study, consult the QAB early in the project to determine the need for a VE study.

Consider coordinating a VE study for projects with total initial cost estimates near but not exceeding the VE cost thresholds. As the project develops and cost estimates are updated the total cost may increase and exceed the threshold requiring VE studies during later phases of the project when study recommendations are more difficult to implement. For more information on cost escalation, see the article, Project Cost Estimation and Management.

A project’s Purpose and Need (P&N) Statement establishes the foundation for successful decision-making and the basis for evaluating and comparing reasonable alternatives. The P&N Statement is used to establish the project scope.

5.1 How is P&N Developed?

To develop the P&N Statement, project data (see the article, Project Initiation) are analyzed to determine project needs. The purpose of the project should be to efficiently address the need(s). For more information on the development of the P&N Statement, see HD-202.6.2, PL-702.2, and the Commissioner of Highways memorandum on Purpose and Need Statement Guidance and Instructions. Other resources include:

- AASHTO’s A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets, 7th Edition, 2018. Section 1.2 Project Purpose and Need.

- KYTC’s Division of Environmental Analysis Project Management Website

- AASHTO’s Practitioner’s Handbook-Defining the Purpose and Need and Determining the Range of Alternatives for Transportation Projects

- FHWA’s Environmental Review Toolkit, The Importance of Purpose and Need in Environmental Documents

- FHWA Environmental Review Toolkit, NEPA Transportation Decisionmaking

Project elements beyond identified needs may be included as project goals and objectives, which may address issues such as quality of life, environmental goals (e.g., avoidance and minimization of impacts and enhancement opportunities), the project’s schedule, cost, quality, cultural resources, habitat, or public input.

5.2 Who Develops the P&N Statement and When?

The project type usually dictates who prepares the P&N Statement and when it is developed. For capital projects, initial P&N Statement development usually occurs during planning.

As potential projects are identified, KYTC planners should identify apparent needs in the CHAF database as a starting point for the draft P&N Statement. Planners generate a draft P&N Statement alongside the initial project concept and document it in planning studies and Data Needs Analysis studies (DNAs).

If a draft P&N Statement is not developed during the planning of a capital project, the project team prepares one during preliminary design. The P&N Statement is refined throughout project development but is considered final after the environmental document is approved and preliminary design is complete. If there are changes to a project and its P&N statement during the final design phase, the environmental document will need to be re-evaluated. The purpose of a reevaluation is to determine whether a completed environmental document or decision requires supplemental analysis.

HSIP and asset management project needs are identified through network screening. Screening is based on a specific performance measure. Most HSIP-funded projects attempt to reduce serious injury and fatal collisions. Road segments with poor pavement ratings are identified annually and pavement preservation and/or rehabilitation projects are developed based on identified needs. Structures are also inspected regularly and assigned structural ratings that are considered when identifying potential structural rehabilitations or replacements.

Most operational and maintenance activities and projects do not require individual purpose and need statements if identified through a program that evaluates the system infrastructure, quantifies the problem, and prioritizes the needs. Individual purpose and need statements may be needed on these types of projects if they involve U.S. Army Corps of Engineers permit applications, historic bridge rehabilitation, and interstate rehab and resurfacing. For more details see the Commissioner of Highways memorandum regarding Purpose and Need Guidance for Maintenance and Operations.

5.3 Why is the P&N Statement Developed?

The purpose directly informs the project scope (and range of alternatives). This, in turn, directly influences the level of effort, cost, and anticipated schedule. All projects that include NEPA documentation must have a P&N Statement.

A clear, well-justified P&N Statement explains funding expenditures to the public and decision makers. For capital improvement projects, the Design Executive Summary (DES) must contain a P&N Statement. If the P&N Statement changes after an environmental document is approved, the environmental document may need to be updated. The PM should coordinate this with the District Environmental Coordinator.

Red Flag

The P&N Statement should not articulate a specific solution to address project needs. It should diagnose the concerns and state what a project should accomplish so that a range of alternatives can be considered to address the need(s).

Performance measures, or measures of effectiveness (MOEs), are quantitative estimates on the performance of a transportation facility, service, program, system, scenario or project relative to policies, goals, and objectives. For more information on the use of performance measures, see HD-202.6.1.

One way to assess an improvement’s effect is to perform a benefit – cost analysis of the improvement that accounts for initial and life-cycle costs.

When establishing a project scope, PMs must gather data on quantitative performance measures (e.g., safety, traffic, structural condition) to assess a facility’s current performance and identify issues affecting the project. To understand the benefits an improvement will confer, PMs should develop forecasts of future facility performance with improvements and without improvements. To analyze current and future performance, PMs need to coordinate with the project team’s SMEs and consider this effort when completing the tasks for the scope of work.

Table 2 provides examples of performance measures that could be identified in the scoping process.

| Table 2. Performance Measures Identified During Scoping | |

|---|---|

| Potential Project Performance Measures | |

| Mobility |

|

| Travel Time Reliability |

|

| Level of Service (LOS) |

|

| Accessibility |

|

| Safety |

|

| Structural |

|

| Pavement |

|

| Infrastructure |

|

Red Flag

Non-compliance with geometric design criteria is not, in itself, a performance issue for an existing roadway. A non-compliant geometric design only needs to be addressed in the P&N Statement if the performance assessment indicates poor performance could be addressed with a specific geometric design improvement. For example, if the lane width is narrower than the recommended design criteria, but the roadway isn’t experiencing high crash rates or issues with traffic operations, addressing the roadway width would be unnecessary.

During the initial phase of each project, PMs need to determine what additional resources are needed to contribute to the development of the project scope and to complete the project.

7.1 Additional Mapping

PMs must submit requests for additional mapping to the Division of Highway Design’s Survey Coordinator. Typically, the Survey Coordinator needs to know the project footprint and the scale of mapping needed. The PM and Survey Coordinator will evaluate the area to determine the type and extent of coverage needed. Making sure enough area is covered significantly reduces the likelihood of needing follow-up mapping. Requests for aerial surveys are submitted before the data collection season, which runs from December through March. Factors such as season, angle of the sun, vegetation, and other issues are critical considerations when scheduling aerial mapping.

Contact the Survey Coordinator if questions arise. HD-308 provides further details on aerial mapping. The District may also have the resources to collect additional mapping.

7.2 Environmental Overview

As soon as possible following project authorization, the PM and District Environmental Coordinator should examine the project area for environmental impacts. These include but are not limited to:

- Air quality

- Aesthetics

- Cemeteries

- Cultural resources (e.g. archeology, historical)

- Endangered species

- Federal lands

- Floodplains

- Groundwater resources

- Hazardous materials and underground storage tanks (Hazmat/UST)

- Noise

- Section 4(f)Includes publicly owned parks, recreation areas and wildlife or waterfowl refuges, or any publicly or privately owned historical sites listed or eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places.

- Section 6(f)From the Land and Water Conservation Act. Applies to all projects, regardless of funding source, that impacts any public park, recreation area or facility acquired or developed with Land and Water Conservation Funds (LWCF). resources

- Socioeconomic concerns and environmental justice

- Streams

- Wetlands

If environmental concerns are detected or perceived, the District Environmental Coordinator should submit a request for investigation to the Director of the Division of Environmental Analysis. The Division of Environmental Analysis provides the results of its investigation and recommendations for consideration. The project team is then responsible for evaluating this information and incorporating recommendations into the project.

HD-400, HD-500, and NEPA Process for Project Managers provide additional information on environmental considerations and permits and certifications. Additional information may also be found in the KYTC’s Environmental Analysis Guidance Manual.

Public involvement is an essential component of project development. Community voices must be factored into the development of the project’s scope. The PM and the District Public Information Officer (PIO) should discuss how public involvement will be conducted on the project as early as possible during project development. If KYTC needs to hold public meetings or hearings, the number and timeframe of these meetings need to be established. HD-600 contains additional information on public involvement.

KYTC’s Public Involvement Plan (see Section 5.1 Project Development) includes information that may be helpful when developing the scope for public involvement activities during project development. It addresses public involvement for planning studies, design, right-of-way acquisition, and utility relocation. Section 5.2 includes considerations related to operation and maintenance activities.

Other deliverables that may need to be considered are a project Public Involvement Plan (PIP) and documentation of public hearings or meetings (Public Involvement Notebook). For more information on PIPs and documentation see HD-600.

Project Manager’s Guidebook – Knowledge Book

AASHTO (2018) A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets, 7th Edition. The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, AASHTO Green Book, Washington DC.

FHWA’s Environmental Review Toolkit, The Importance of Purpose and Need in Environmental Documents

FHWA Environmental Review Toolkit, NEPA Transportation Decisionmaking

KYTC’s Highway Design Manual

KYTC’s Planning Guidance Manual

KYTC’s Environmental Analysis Guidance Manual

Project Management Guidebook Knowledge Book:

Access the complete Knowledge Book here: Project Management Guidebook

Next Article: Project Schedule & Development of Milestones

Previous Article: Project Initiation